Abstract

This thesis presents an in-depth exploration of gathering as a creative process within the digital realm. Through the investigation of User-Generated Content (UGC) platforms, this study examines how interviewed artists, designers, and developers are using these platforms as “digital gardens”, i.e. online containers to cultivate over time curated references that reflect their visual culture. The research secondly sheds light on the crucial role of specific platforms, in turn influencing creative processes, intertwining visual culture, ownership, content curation and collaboration, platform design, and usability. It therefore aims to thematize emerging tension points, unraveling the impact of these platforms on creativity, knowledge cultivation, and the complexities of managing diverse digital information spaces.

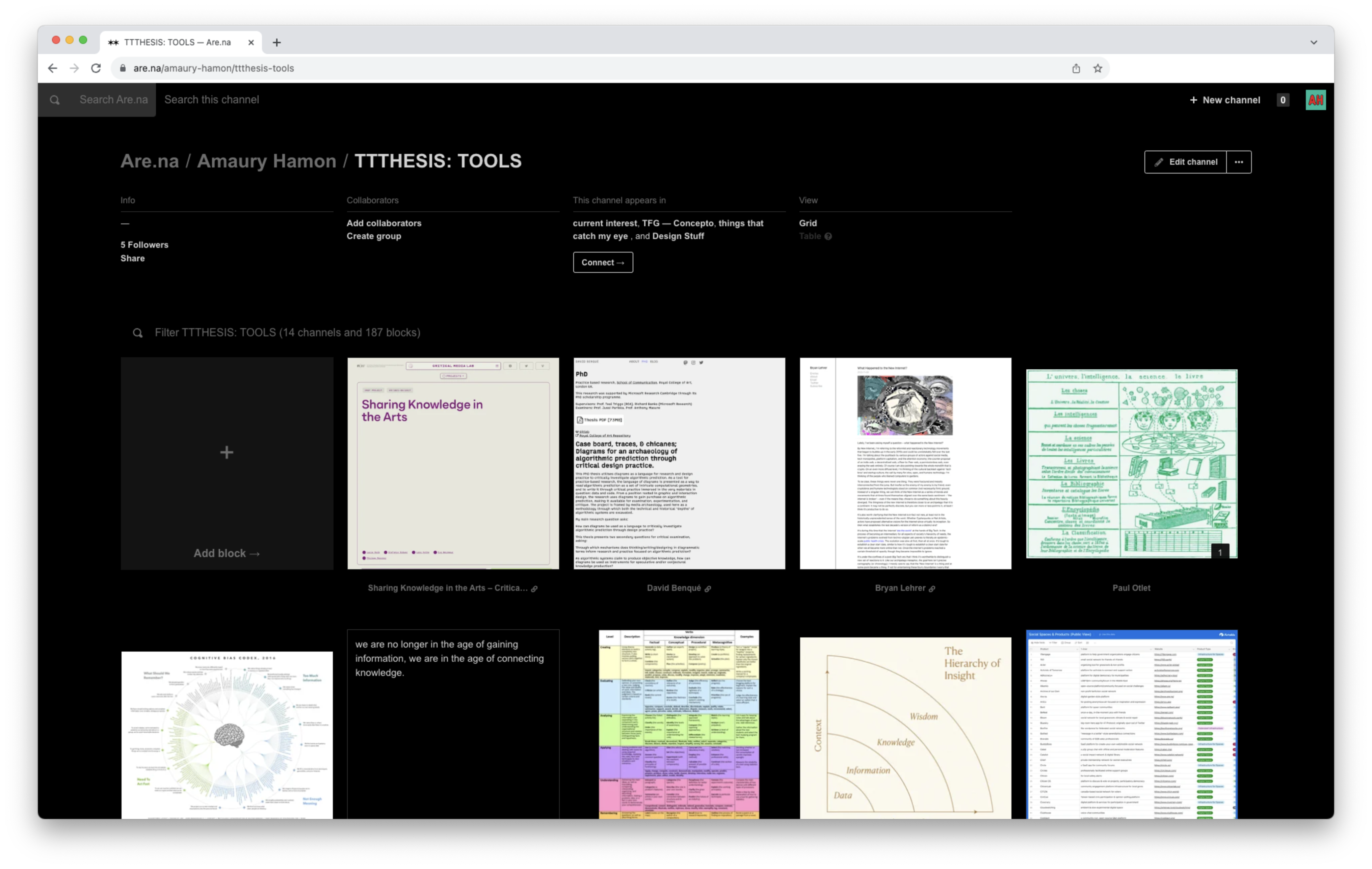

Examining the collaborative aspects of gathering, with the case study of Are.na (2012), this study navigates the transition from individualistic creative processes to more inclusive models of collaborative commons through sharing within UGC platforms. Despite their inclination towards privacy, these platforms paradoxically foster external source interconnections, emphasizing broader themes of sharing, open-access culture, and redefining ownership dynamics. Through an analysis of platform challenges and radical initiatives promoting personal web spaces, it explores cultural shifts, ownership dynamics, and the economic implications of shared creative processes and resources, hinting at potential collective knowledge growth.

Keywords

Collection, Gathering, Sharing, Knowledge, Digital Gardening, User-Generated Content, Online platforms, Curation, Collaboration, Public Learning

Introduction

This master’s thesis explores the potential offered by online collaborative platforms in facilitating creative processes, examined through qualitative interviews involving artists, designers, and developers. With the emergence of Web 2.0 (2003) and subsequent User-Generated Content (UGC) platforms like Tumblr (2007), Pinterest (2010), and Are

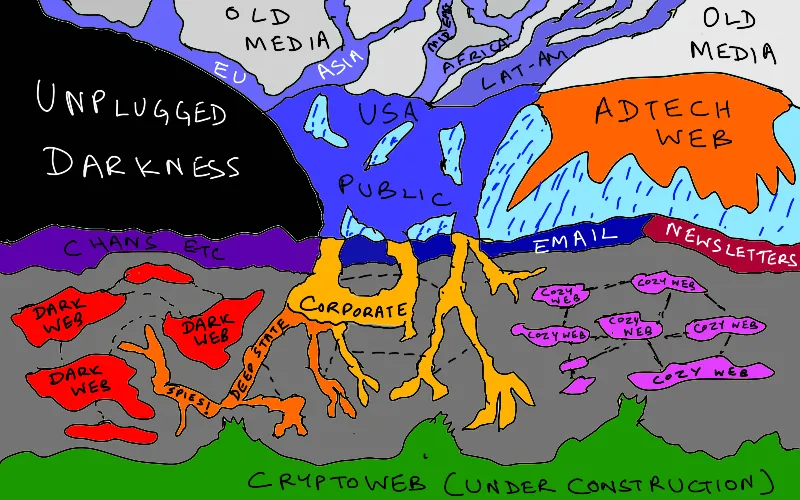

If the beginnings of the Internet were accompanied by an ideology of accessibility and sharing comparable to a new form of public space, referred to by founder of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee Tim Berners Lee in front of the World Wide Web, 1989, ©CERN. as “a collaborative medium, a place where we [could] all meet and read and write.”1, its development, including UGCs, is a form that refutes this principle. Owing to advancements in recommendation algorithms, miniaturization of hardware, wireless connectivity, and expanded data storage capabilities, most current UGC platforms exist as private data repositories within the corporate sphere of the Web, predominantly centralized by tech giants like GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, etc.).

Tim Berners Lee in front of the World Wide Web, 1989, ©CERN. as “a collaborative medium, a place where we [could] all meet and read and write.”1, its development, including UGCs, is a form that refutes this principle. Owing to advancements in recommendation algorithms, miniaturization of hardware, wireless connectivity, and expanded data storage capabilities, most current UGC platforms exist as private data repositories within the corporate sphere of the Web, predominantly centralized by tech giants like GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, etc.).

Web 2.0 also witnessed the rise of mobile devices, altering user interactions. In December 2010, desktops held 95.9% of the market share compared to mobile’s 4.1%, but by September 2023, mobile devices claimed a 53% share2. The decline of the World Wide Web is attributed to the surge in dedicated mobile applications released by device manufacturers’ application stores such as Apple’s App Store or Google’s Play Store (both 2008), overshadowing traditional web usage and aligning with the dynamics of platform capitalism. As asserted by Knopf3, the structure of social media platforms is engineered to retain users within these “walled garden” enclosed environments, solely focused on content consumption, rather than interconnection.

UGC services and networks foster a notion of a somewhat ambiguous “semi-public” digital space for human interaction, as highlighted by Ertzscheid4. However, these platforms, according to Tariq Krim’s Slow Web Initiative5, are “greedy for our data”, confining interactions and content behind barriers, via restricting access, relying on user data consent, offering limited free access (freemium), premium subscriptions, or demanding attention in exchange for access. Whereas, according to Jenny Odell:6

A public, noncommercial space demands nothing from you in order for you to enter, nor for you to stay; the most obvious difference between public space and other spaces is that you don’t have to buy anything, or pretend to buy something, to be there. –Jenny Odell

But throughout the interviews and the Web, Are

A garden draws a sense of public view and access. Commonly defined as a “rich-well cultivated region” where things are “cultivated”, they can be displayed “[…] so that the public can go and see them [plants and flowers].”10 Out of this context, radical handmade11 and public uses of the Web re-emerge, reminiscent of the Web’s early vernacular days.

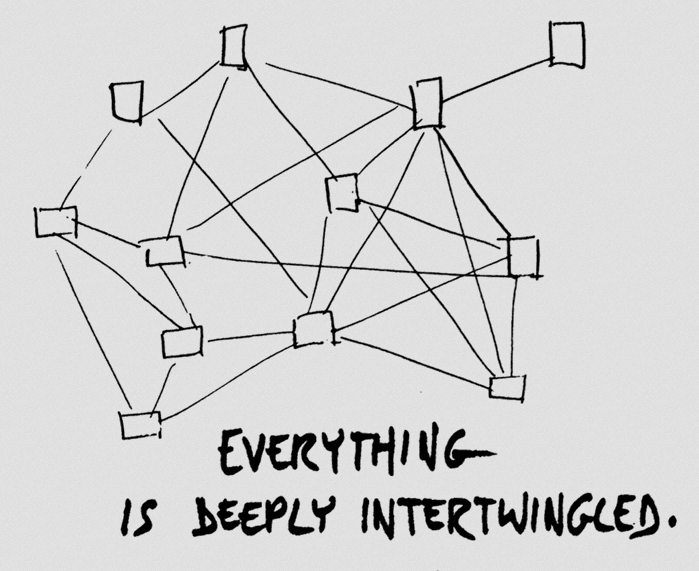

The individually-scaled practice of Digital gardening then, refers to planting seeds, cultivating knowledge over time, on your fully owned and handmade corner of the Web, without restrictions to specific platforms or technologies. It is another neologism to the list of nature-inspired terms to describe technological actions and methods, dating from the nineties via Hypertext Gardens12 (1998), early Hypertext (1965) experiments within the Web by Mark Bernstein. The essay metaphorically featured topics of free internet exploration within open gardens and wilderness. While being less centered on building personal digital spaces, it emphasized the experience flows and how Web contents could be organized.

Re-emerged in 2015 by Mike Caulfield’s conference and essay13The Garden and the Stream, a Technopastoral, Caulfield underlined the need to reclaim independent ownership from the corporated Web platforms and social media, by setting up a personal yet public digital space of knowledge curation on the Web, for content to be de-streamed from algorithmic feeds and cultivated over time.

Therefore, the research question I endeavor to answer is:

How using online user-aggregated content platforms and digital gardens to gather and share knowledge can transform (or not) a creative practice?

This question will address the ambiguous tension point of how creatives actively use those platforms, versus how those platforms develop passive influence on their processes in return.

Passively liking an image is not the same as connecting it to a curated folder actively defined by the user. Is the platform open-ended or restrictive for how one can use it? What is the focus or purpose of the platform? The scale and diversity of the population of the platform are also highly linked to what content (its quality and context) is generated on it. To what extent the platform allows the interconnection of Web contents outside its walls? To what extent the platform gives a sense of ownership to its population to steer the direction of the platform? What is the method of communication between members on the platform? Is it considered introverted, with minimal features, or extraverted with full multimedia communications? In this sense, does the platform allows meaningful ways to be alone on it? Last but not least, do the platforms target individual gain or encourage collective gain interacting with other members’ content?

To answer this investigation, nine qualitative interviews of Western Europe-based artists, designers, and developers were conducted on their general online creative processes, and more specifically on the Are

The aspects of creative processes in focus regard how interviewees, beyond their craft, practice what Nicolas Nova calls “Research-Creation”, i.e. to develop and renew knowledge through tactics, tools, observation, exploration, and combination of ideas and concepts.14 I believe the exploration online regarding the browsing, curating, and storing of references, to develop visual or literacy culture is key to investigating: which are the end goals, and to what extent interviewees exchange, collaborate, contribute, and share publicly–actively or unconsciously in their process. The interview kit helped the thesis to get insights and tension points such as topics of the intimacy of ideas, originality and legitimacy, gatekeeping, or contributing and sharing publicly.

Developing a creative’s visual culture online–as is the case offline–implies spending time and consuming content shared by others, to “absorb”, i.e. curate and collect what can fuel inspiration, and lead to new knowledge and ideas. Considering the online space as a pool of aggregated visual culture already there, why would creatives use it only one way and not contribute more actively with their self-made collections?

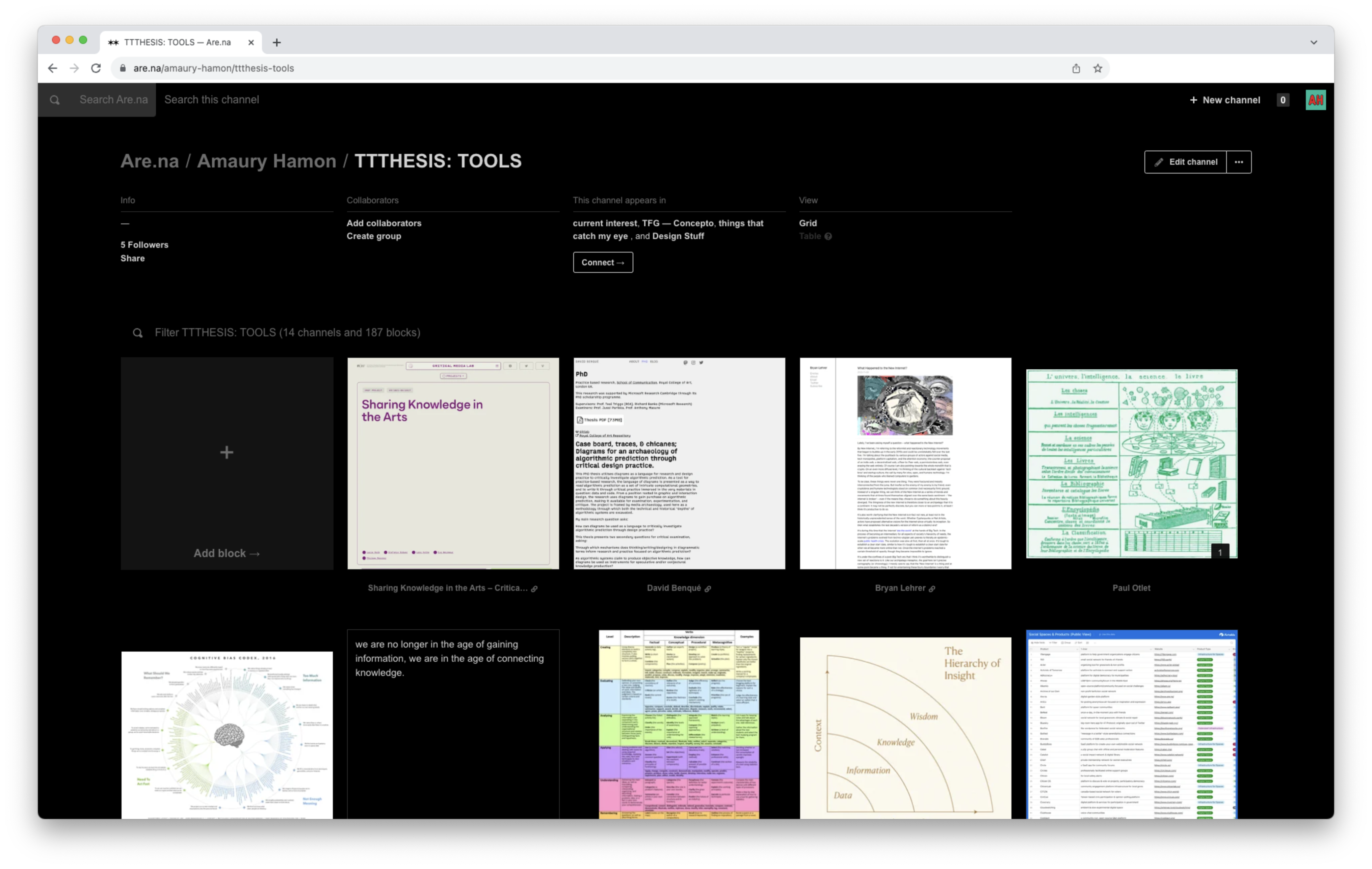

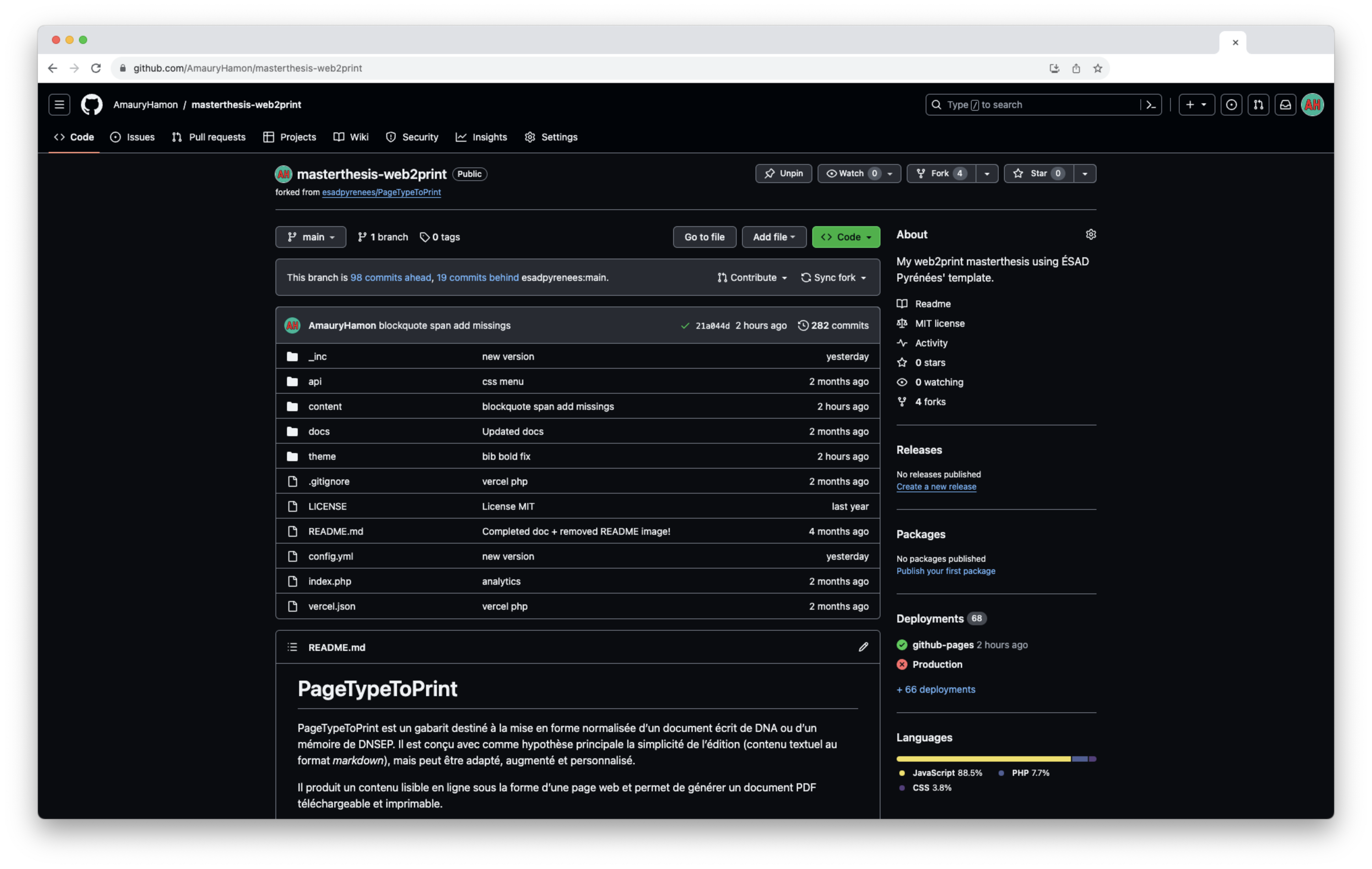

This MA thesis is designed as a website-first output, to shape a form meaningfully suitable to its content. Using web-to-print features (more on this process available in the design notes appendice), it allows for anyone to print freely the research in A4, supporting universal access when unfortunately, most academic writings lack a broader audience due to limited online presence, enclosed access to academic platforms, and lack of PDF indexation in search results. In an echo of the aggregated platforms investigated and the digital gardening approach, this thesis was fueled by gathered references in a dedicated public Are

Gathering as a radical creative process

This chapter embarks on a nuanced exploration of gathering as a radical creative process in the digital realm. From Le Guin’s perspective to evolving contemporary digital gathering methods, it dissects how platforms redefine authorship and emphasize collective efforts within a container-content paradigm. With diverse perspectives from nine Western-based creatives interviewed, this chapter illuminates the shift from traditional to online methods. It scrutinizes the role of specific UGC platforms in the creative process, used for curation and collaboration on creative content gatherings. Therefore, it unravels their impact on creativity, knowledge cultivation, and the complexities in managing information across varied digital spaces, as well as the intricate relationships between visual culture, content curation, and platform usability.

On Gathering

Designer Mindy Seu roots Ursula K. Le Guin’s gathering practice and extends it to a contemporary approach in the digital age. Le Guin in her book Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1986) brings perspectives on the notion of collection and gathering, stating the first human tool was a basket, a tool for communion, rather than a spear, a tool for domination. It then places the protagonist in narrative structures as a gatherer rather than a hunter.16 To this aim, Le Guin emphasizes the significance of gathering, collecting, and sharing. This vision supports the idea of a collection working towards collective good expressed by Daniel and asks questions about the role of the collector, and also the form of the container gathering such collections. The carrier bag, in this context, becomes a symbol of collection and preservation—a vessel for holding various elements that contribute to the sustenance and enrichment of a community. Le Guin’s theory challenges the dominance of the hero’s narrative and highlights the importance of collective efforts, cooperation, and the sharing of resources and knowledge.

In her essay On Gathering17, Mindy Seu defines the process of gathering to “aggregate, together with collaborators, disparate pieces from an ecosystem, and develop the appropriate container for each collection.”

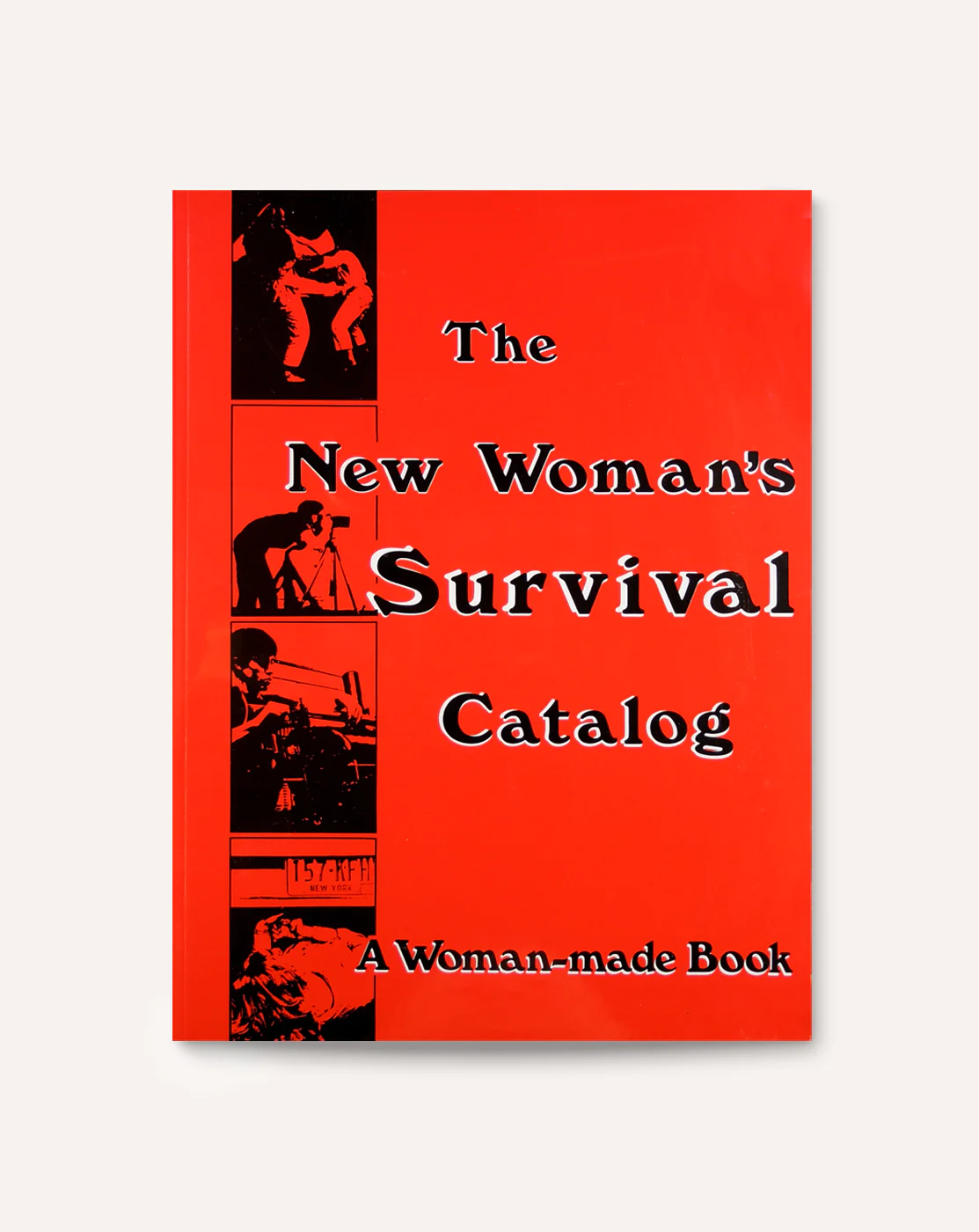

Moreover, she explores how digital platforms and online events have transformed the way people gather and share information. Bringing different examples of collective collections, such as the New Woman’s Survival Catalog, Cover of New Woman’s Survival Catalog, 1973, by Kirsten Grimstad & Susan Rennie. promoted as a "feminist Whole Earth Catalog

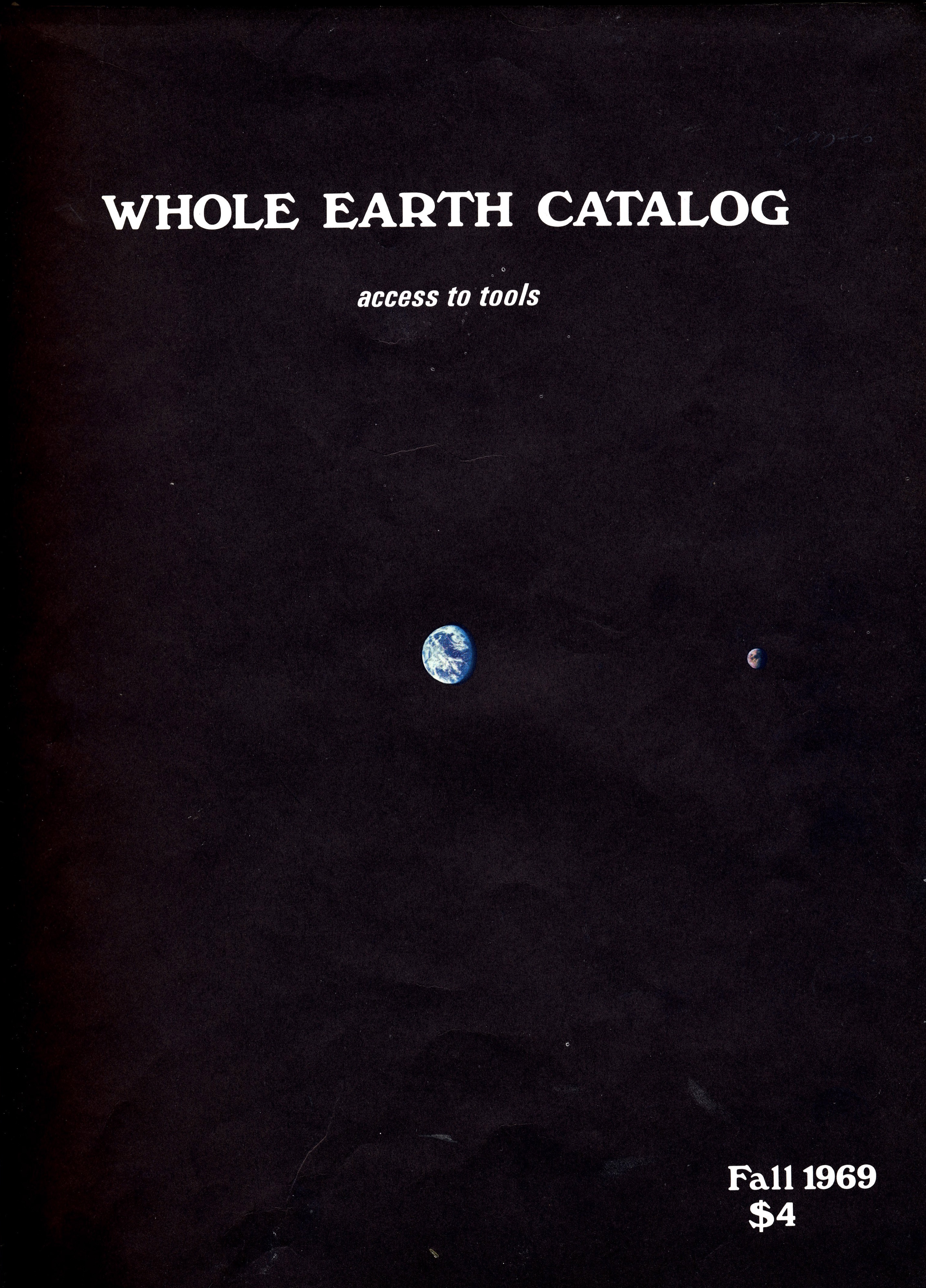

Cover of New Woman’s Survival Catalog, 1973, by Kirsten Grimstad & Susan Rennie. promoted as a "feminist Whole Earth Catalog Cover of the first issue of Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand, 1968.", and the Cyberfeminism Index

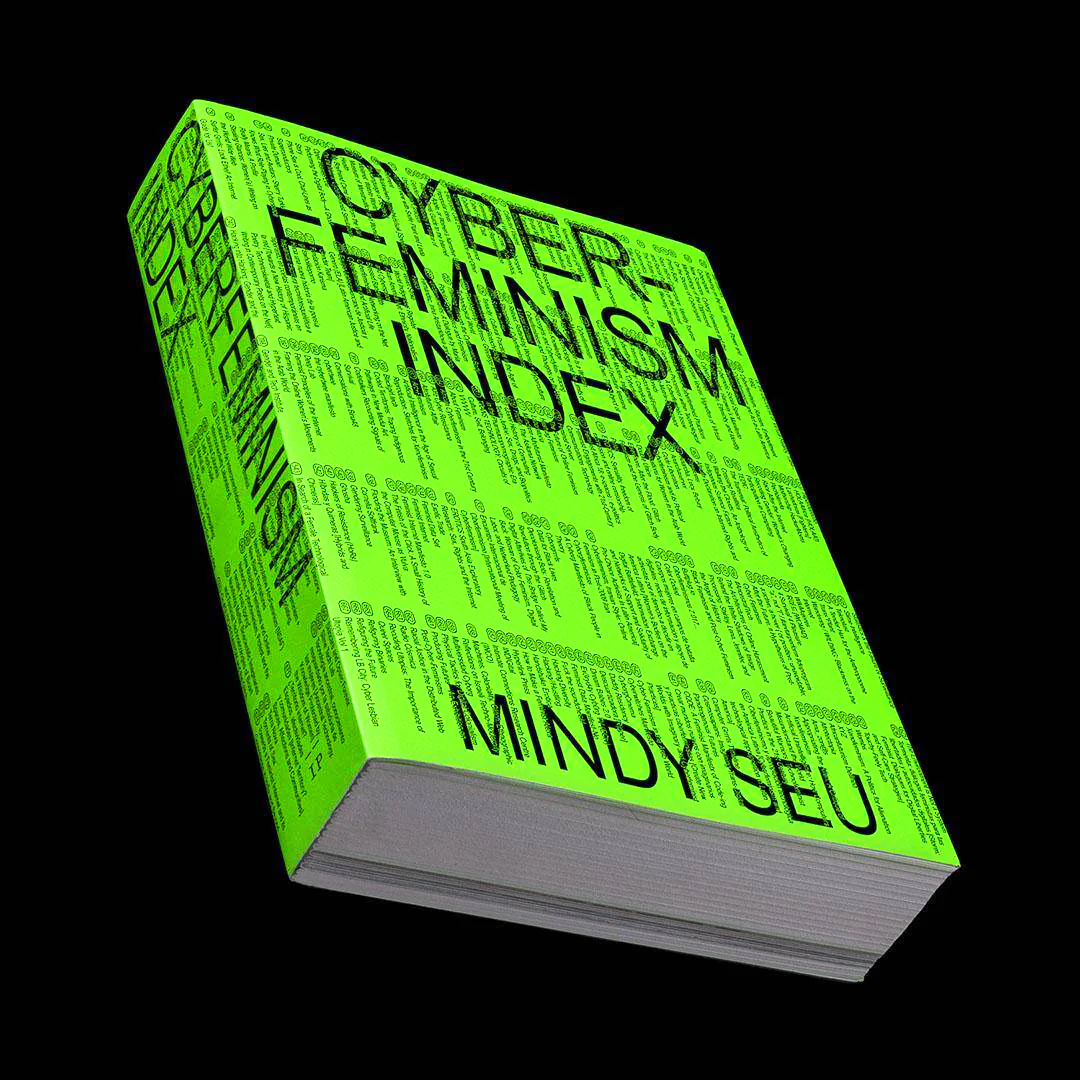

Cover of the first issue of Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand, 1968.", and the Cyberfeminism Index Cover of Cyberfeminism Index, by Mindy Seu, 2022., Seu explores the evolving nature of gathering, blurring the lines between container and content, and challenging the traditional notions of fixed, solitary authorship, as she states:

Cover of Cyberfeminism Index, by Mindy Seu, 2022., Seu explores the evolving nature of gathering, blurring the lines between container and content, and challenging the traditional notions of fixed, solitary authorship, as she states:

Gathering stories is radical because it refuses to give the gatherer all of the credit. The collector-collection dynamic is deliberately broken. The person who puts it together is only one of many parts. –Mindy Seu

Gathering therefore challenges the conventional notion of individual credit or authorship. It underscores the idea that the person collecting or assembling isn’t the sole creator or authority behind it. Instead, it emphasizes the collective nature of gathering, where contributors, narrators, and various sources play essential roles in shaping the narrative. It is relevant to creative processes because it questions the traditional concept of a single author being solely responsible for creation. It highlights the importance of acknowledging the multiple voices, perspectives, and contributors involved in creative endeavors, advocating for a more inclusive and collaborative approach to creation. This perspective resonates with the ethos of collective participation and shared credit, emphasizing the richness that emerges from diverse contributions and collaborative efforts that can be leveraged on UGC Platforms for creatives.

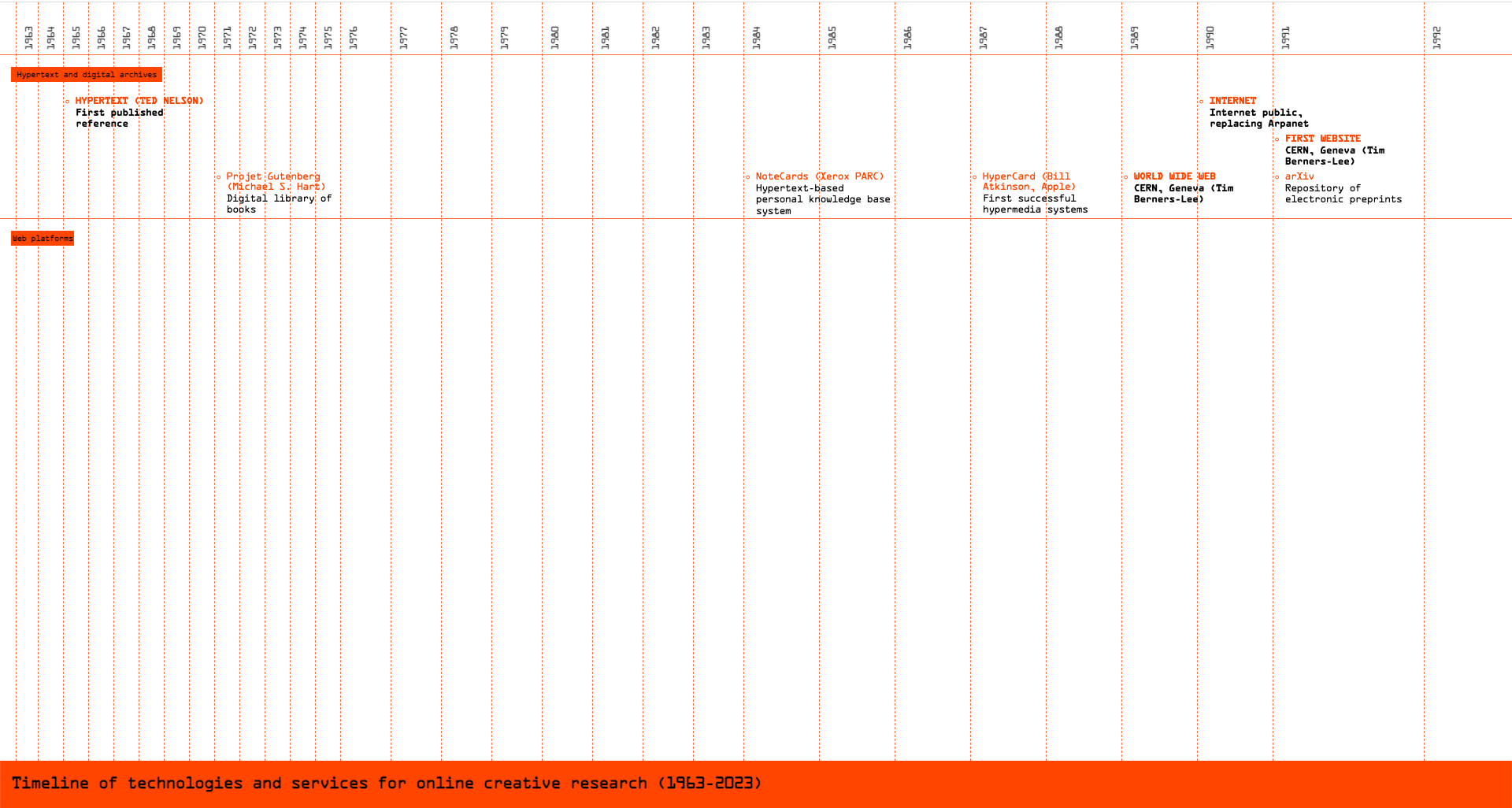

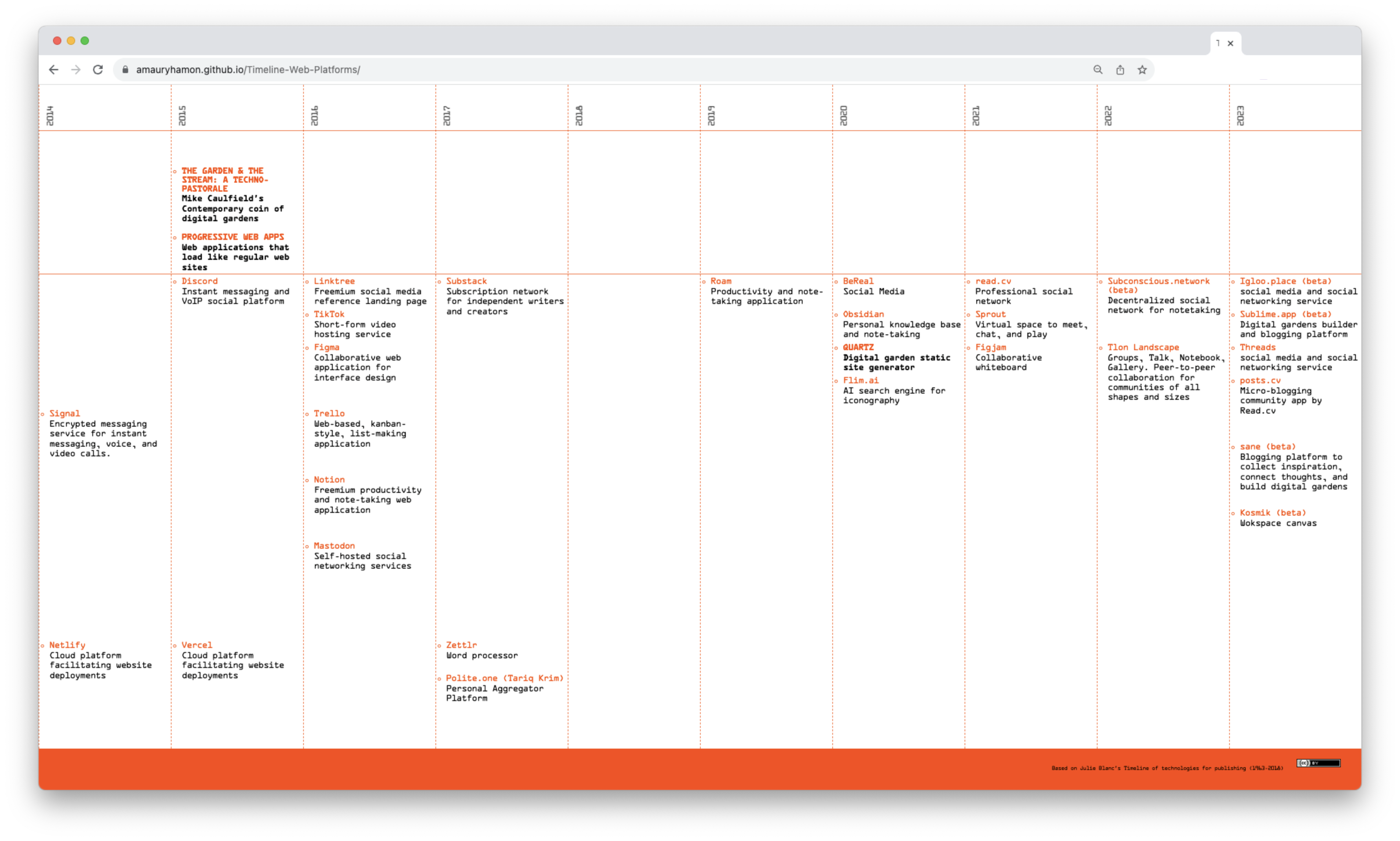

The following timeline Timeline Link18 aims to historicize the evolution of digital platforms and archives, from Ted Nelson’s Hypertext (1963)

Timeline Link18 aims to historicize the evolution of digital platforms and archives, from Ted Nelson’s Hypertext (1963) Drawing of Ted Nelson in Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1974. to the proliferation of current digital platforms forming the Centralized Enclosed corner of the Corporated Web. In this timeline are emphasized: major technology and platform evolutions, platforms related to creative processes mentioned in the interviews. The overall reflects a rise of smaller independent platforms after the boom of major social networks.

Drawing of Ted Nelson in Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1974. to the proliferation of current digital platforms forming the Centralized Enclosed corner of the Corporated Web. In this timeline are emphasized: major technology and platform evolutions, platforms related to creative processes mentioned in the interviews. The overall reflects a rise of smaller independent platforms after the boom of major social networks.

Digital gathering methods as means to collect knowledge

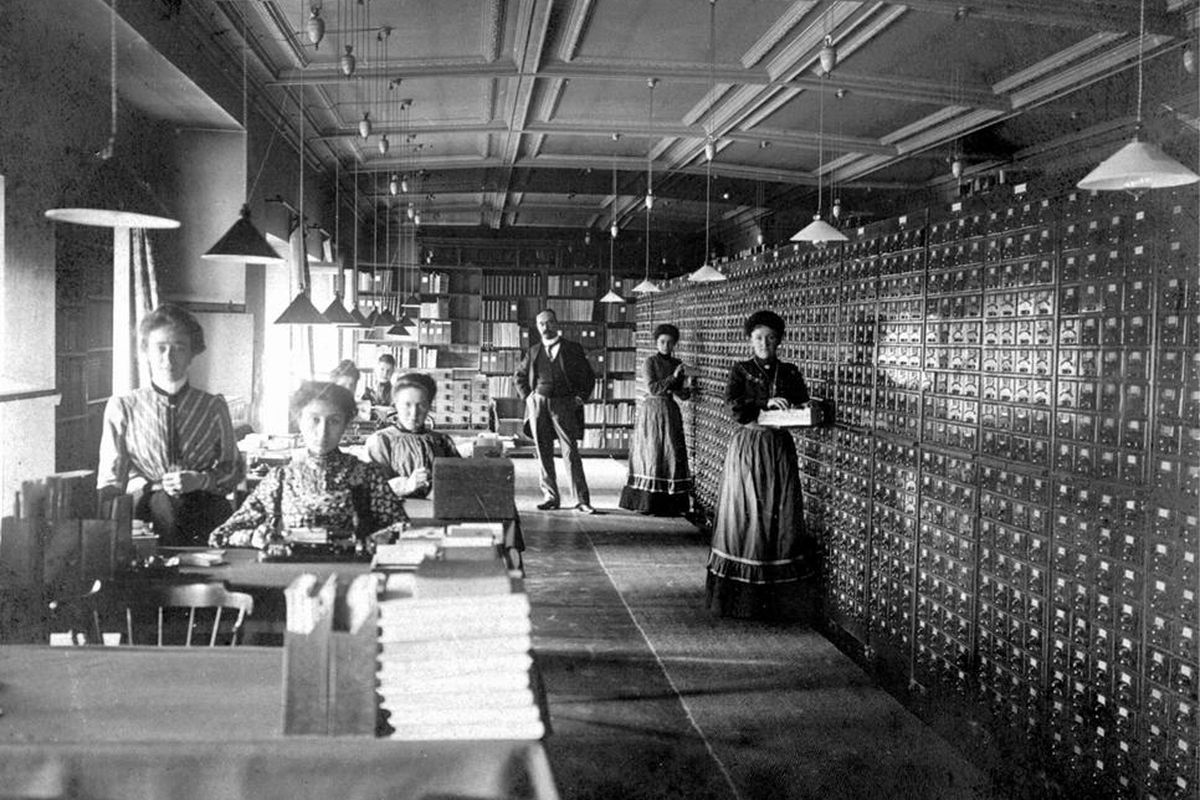

Interviews conducted with nine European-based creatives (artists, designers, developers) in the summer of 2023 highlight the diversity of digital gathering methods and motivations. Assessing the transformation of creatives’ gathering methods into the digital landscape, they explored the shift from traditional to online gathering methods, emphasizing the role of UGC platforms or digital gardens in personal or collective knowledge curation, privately or publicly. Contrarily to the vertically defined classification of 20th century Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum  Mundaneum, founded by Paul Otlet, 1919–34, Belgium. analog knowledge archives, Some UGC Platforms allow interconnection of content, for users to freely constitute their curation into a self-labeled knowledge base, by either uploading or connecting any content found online either inside the platform or outside.

Mundaneum, founded by Paul Otlet, 1919–34, Belgium. analog knowledge archives, Some UGC Platforms allow interconnection of content, for users to freely constitute their curation into a self-labeled knowledge base, by either uploading or connecting any content found online either inside the platform or outside.

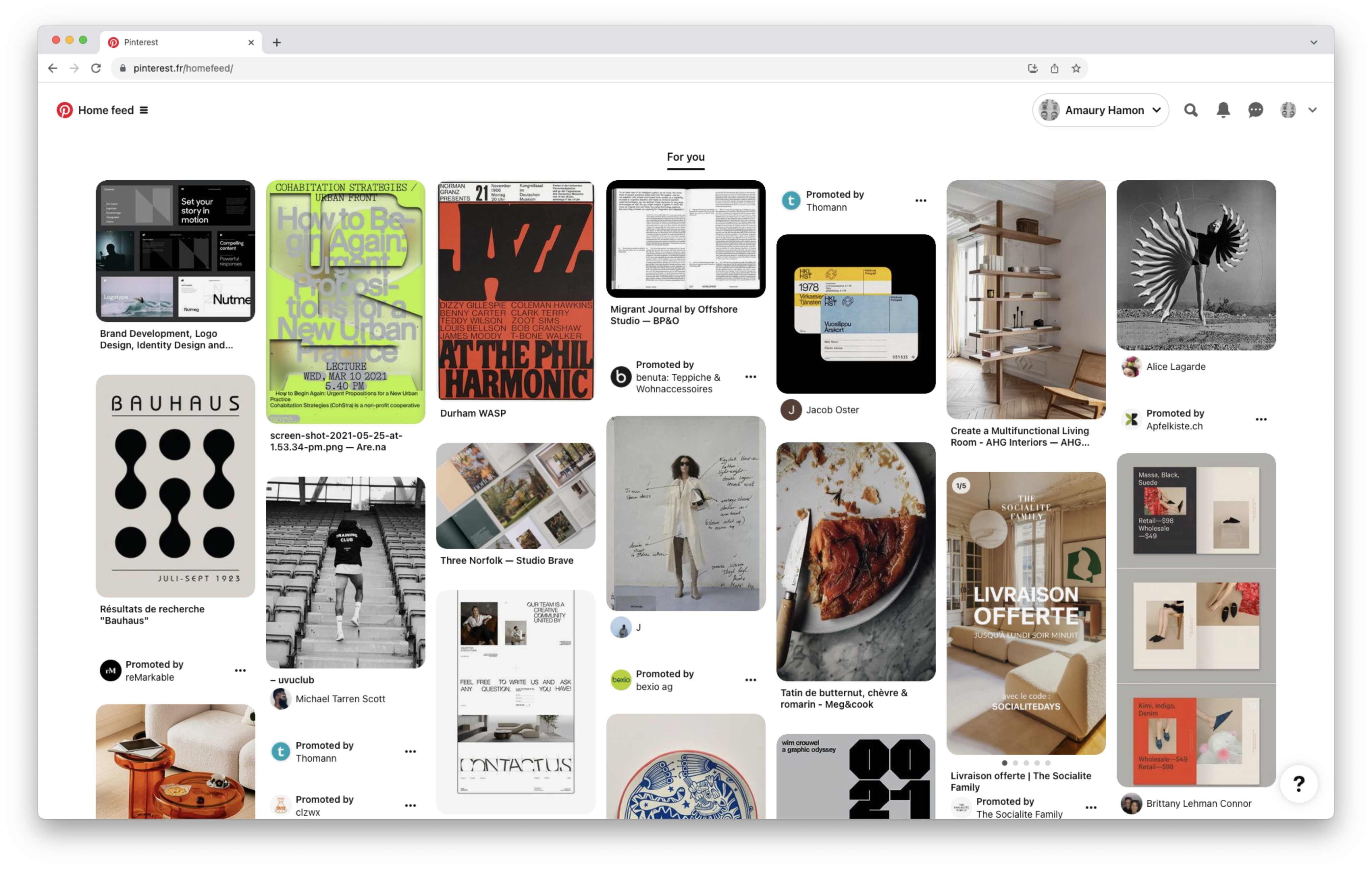

While browser tools, social media, journaling, and search engines are indeed recurrent within creative processes, a key typology of platforms for collection and curation refers to visual discovery engines, such as Pinterest with its masonry grid feed of images, Tumblr with its vertically-stacked stream of blog content, and Are

In common sense, making a collection would mean bringing together elements due to their value, attractiveness, or interestingness, “over a period of time”, “for study, comparison, or exhibition or as a hobby.”19 A collection could bring quite disparate elements while sharing a few common points, or associations. Emphasizing the way of thinking, the connections, and associations, are key to considering how creative practices collect, and connect by association, to grow and organize knowledge over time, and to develop documentation, new skills, crafts, or ideas. As Swiss curator, critic, and historian of art Hans Ulrich Obrist20 implies:

To make a collection is to find, acquire, organize, and store items […]. It is also, inevitably, a way of thinking about the world–the connections and principles that produce a collection contain assumptions, juxtapositions, findings, experimental possibilities, and associations. Collection-making, you could say, is a method of producing knowledge. –Hans Ulrich Obrist

Similarly to Obrist’s definition of collection, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defines creativity as expressing unusual thoughts and helping experience the world in novel ways, implying originality, and playfulness.21Creative processus then, can be referred to as a form of inquiry and collection that goes beyond traditional, empirical methods and incorporates creative tactics and artistic exploration. Associated with fields such as the arts, design, and humanities, the goal is therefore not only to discover new information but also to generate novel ideas, perspectives, or expressions, to share information, through art-based production or building knowledge.

Perspectives from Creative Practitioners

Toolbox and processes

This online gathering and collection-making process of creatives, as a means to fuel visual culture and generate knowledge, is firstly echoed in several steps by one of my interviewees, Florian Hilt, 3D artist and photographer based in Lausanne. By first pooling visual cues from a plurality of algorithmic feeds (Instagram, Twitter and TikTok), he then merges his findings into curated Are

I’m based on a notion of micro-universes and the theory of attraction and repulsion. What interests me a lot when I have access to all this content is to be able to mix it together. It helps me to create projects as I’m building by association and repulsion of ideas. –Florian Hilt

UGCCCC platforms could therefore help creatives to create compatible containers for gathering and building their personal knowledge, free of imposed classification systems and norms. Yet, they raise challenges in the endeavors to manage and organize information across multiple platforms, sometimes leading to chaotic methods as artist Lucas Erin states:

I use several of them on a seasonal basis, but then I have a real problem mastering this data. My problem is that I have physical sketchbooks, I use Notes quite a lot on my iPhone and then on the other side I have a Pinterest folder and then a folder on Instagram, and then behind that there’s Are

.na . It’s all a bit mixed up. Not to mention the InDesign documents in which I try to make pdfs mood boards… My use of platforms is completely chaotic. –Lucas Erin

According to Jonas Pelzer, Berlin-based designer and developer, some platforms feel more suitable than others, while Daniel Robert Prieto, London-based Creative Director and curator of the graphic design-oriented Tumblr This is Grey, underlines the interface ease of use:

I tried multiple research tools in the past, but most of them don’t exist anymore. But I always came back to a non-collaborative standard setup with bookmarks and notes before using Are

.na , which is the first platform I’m really happy with. […] In addition to my notes app and my analog notebook, I mainly use Are.na for research and organization. I also use Twitter, Mastodon and Instagram, but I don’t consider them comparable. I sometimes look for specific resources on Twitter and Mastodon but that’s as far as the research part goes. –Jonas Pelzer

Tumblr. Why do I like it? Because it’s just one big stream of images, it’s so simple. There are tools for downloading the whole of Tumblr. –Daniel Robert Prieto

Some interviewees also quote recurrent platforms and sources of inspiration, using models of subscription, to maintain a controlled curated news feed center when subscribed pages update new content. Via RSS (Really Simple Syndication) technology for American artist Baker Wardlaw, or specific blogs via Tumblr for industrial designer Aurélie Vial:22

There’s a Tumblr I think I’ve been going to for ten years because it’s a source that’s reliable for me. It’s still nurtured and active. And the quality of the image compilation is pretty constant. I mean, it’s never disappointed me. –Aurélie Vial

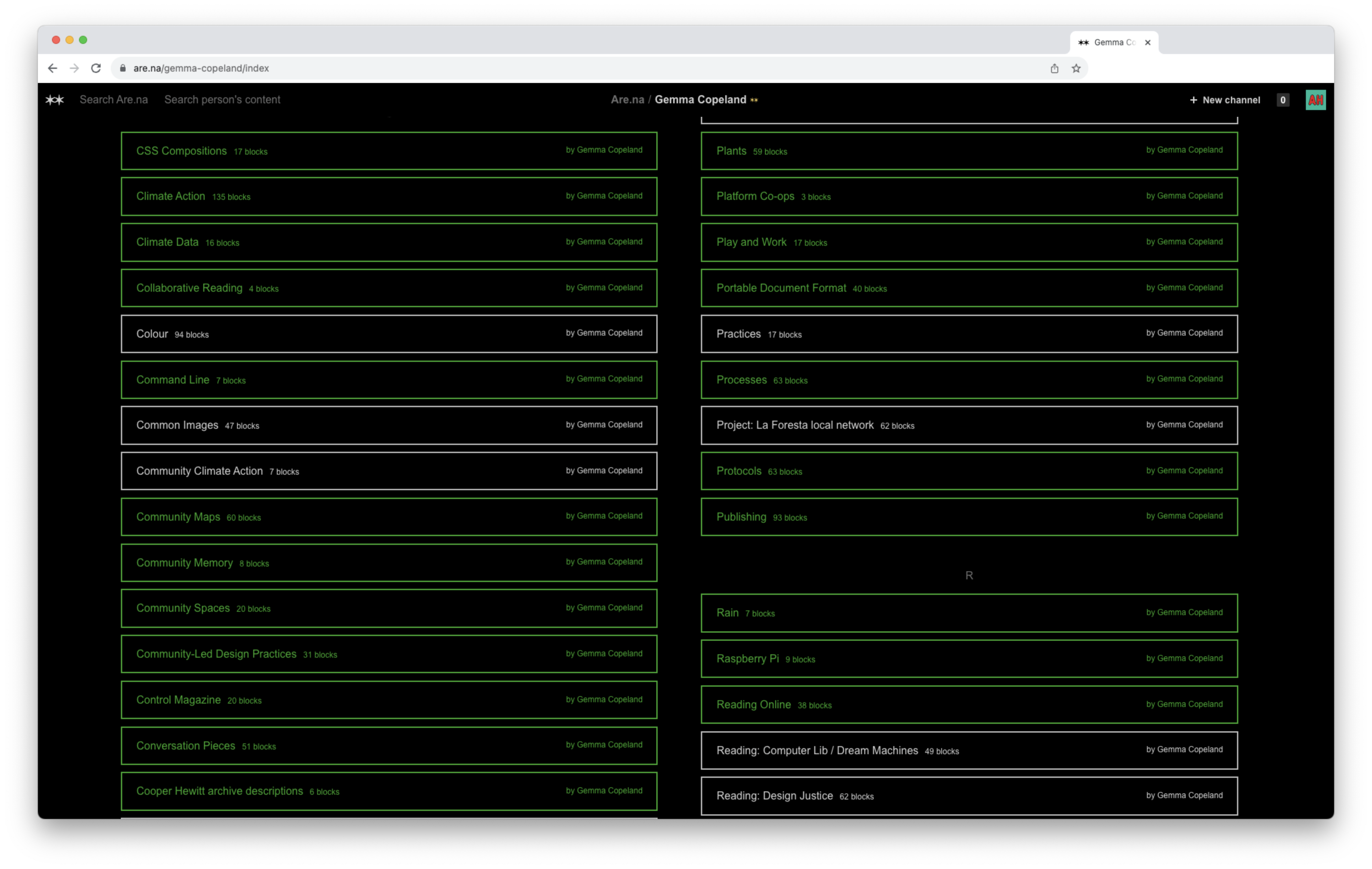

Using tools does not have to be by default and one may not suffice. Most of the interviewees generally research through a combination of platforms to develop a singular process. The choice of a specific platform can come out of curiosity about the latest tool, or some interviewees have a rather opinionated approach to selecting them, as explains Gemma Copeland, Lisbon-based Australian designer and member of Common Knowledge, a not-for-profit worker cooperative:

For Common Knowledge we use so many tools. Over the last couple of years, we spread out from wanting this big monolithic tool that does everything. This kind of generalist approach of trying to be this all-in-one thing is not the best because it doesn’t do anything well. Tools that do one thing well, but are interoperable with other tools, I think that’s the gold standard. We like tools that are quite opinionated, particularly those that are not about trying to get your attention all the time. So, for example, we don’t use Slack. –Gemma Copeland

All-in-one organizational tools such as Notion (2018) or Linear (2019) were mentioned by Frederik Mahler-Andersen, Gemma Copeland, and Daniel Robert Prieto, whether it is for project management, note-taking code snippets, agenda, or maintaining personal CRM.23

Online browsers already allow native functionalities such as bookmarking and saving images on local folders on one’s device, which in my own experience was the very first method I used while starting my studies in Art and Design. In addition, search engines such as Google Images search–heavily used by Aurélie to source images found on UGC platforms–are also one of the most basic approaches to practice visual discoveries, before accessing more specific photo-sharing platforms such as Flickr (2004) or visual search engines platforms such as Pinterest, more convenient for creatives to develop visual culture. As Brussels-based designer Émilie Pillet states:

I record a lot of references. It’s a lot easier to create this sort of local library on my computer and remember where things are than an online platform where I’ll quickly forget what I’ve seen. –Émilie Pillet

In addition to a preference for more tangible containers of inspiration, Émilie emphasizes the printed objects inspiring her “more than platforms”, as better curated flows of references, redistributing the value of her used platforms for storage, if not made on her computer. Daniel Robert Prieto reflects on his pre-WWW early print-only gatherings:

When I was 18, 20, the only way was design books. I spent an insane amount of money just buying design books […] spending days and days in the design library, going through books, buying, sharing, with other friends, exchanging books, that was the place to eat design, absorbing design. […] The book in itself is curated, in an order, it is selected, and it’s around a topic. You take that for granted, you think that reality is like this. When you go to the internet, that curation doesn’t exist. It’s a bucket. –Daniel Robert Prieto

Challenges of passive gathering and context collapse

Social media such as Instagram (2010), X (Twitter, 2006), TikTok (2016), and Fediverse Mastodon (2016) propose endless algorithmically filtered streams of time-bound content. In those, the use of features such as recommender systems, likes, favorites, hashtags, comments, and followers can be used to store references and connect with their creators. As Florian Hilt states, his gathering method passes through the passive visual trigger of the like button, helping him to maintain a history of his latest liked posts: “On Instagram, you can access your likes, up to three hundred, which I find quite good for my methodology because it allows me to renew myself and not go back too far in time.” Similar visual trigger methods–between obsessive consumption and productive death-scrolling–were discussed by Daniel R. Prieto regarding his navigation of the Tumblr feed:

The reason I was using Tumblr was the shortcuts. I could go with “J” and “K”. I think “K” was to save it, and I could go very quickly. I couldn’t go with the mouse. –Daniel Robert Prieto

Similar time-bound feeds of content can be seen in chat applications, in which Discord (2015) and Meta’s WhatsApp (2009) for example, can be used to share references and interact with people about them. Lucas Erin for example, regularly sends to fellow practitioners references through chat to later on create moments of discussion in real life. To further add possibilities of chat exchanges of references, WhatsApp iOS24 rolled out this year features such as text detection in images, allowing for instant lookup and translation.

Algorithmic feeds are designed to stimulate the constant use of an application and maintain the attention of the user through ever renewing what is shown to the user. With advances in algorithms, feeds using recommender systems moved out of initial chronological manually curated feeds, which could lead to feeling trapped in aesthetic bubbles, and losing personal need for control in curation expressed by Émilie:

I would never use Pinterest, for example, to look for references. I have the impression that with all the platforms, it sends back the same references and the same aesthetics. –Émilie Pillet

The mentioned platforms are not without detriments to creativity. Specific issues of context collapse are widely expressed from the overwhelming consumption of content tending to lack source and context.

According to Daniel, “Images on the internet don’t have any context. They don’t have a story. They don’t have a client. They have nothing. They’re almost like in an empty museum.” Aurélie states that on Are

I feel that part of my job is to go and find it. So I wonder how it’s offered to me, and if it’s offered to me, is it offered to everyone else? […] I like the idea of being a bookworm to find information. And the question isn’t necessarily whether it’s true or not, it’s rather what I do with it and how I transform or use it. –Lucas Erin

Gemma suggested her blogging as a radical alternative, not only to better contextualization but also to better appropriation of her references, and escape from the platform feeds by having a fully-owned space. Using whatever platform exists, even if multiple, is indeed radically different than having your own. Gemma’s blog25 is not aiming to “necessarily produce original ideas because nothing is original, everything’s a remix. But at least, to kind of draw out those threads and spend a bit more time on them and go further with the curation.” As she states:

Part of wanting to build a blog was that my practice was too much just collecting and consuming, and it felt in a way passive, and not ever working through in greater detail what I thought about things, almost going too far onto this kind of intuitive collecting and not enough synthesis and articulating my own point of view. –Gemma Copeland

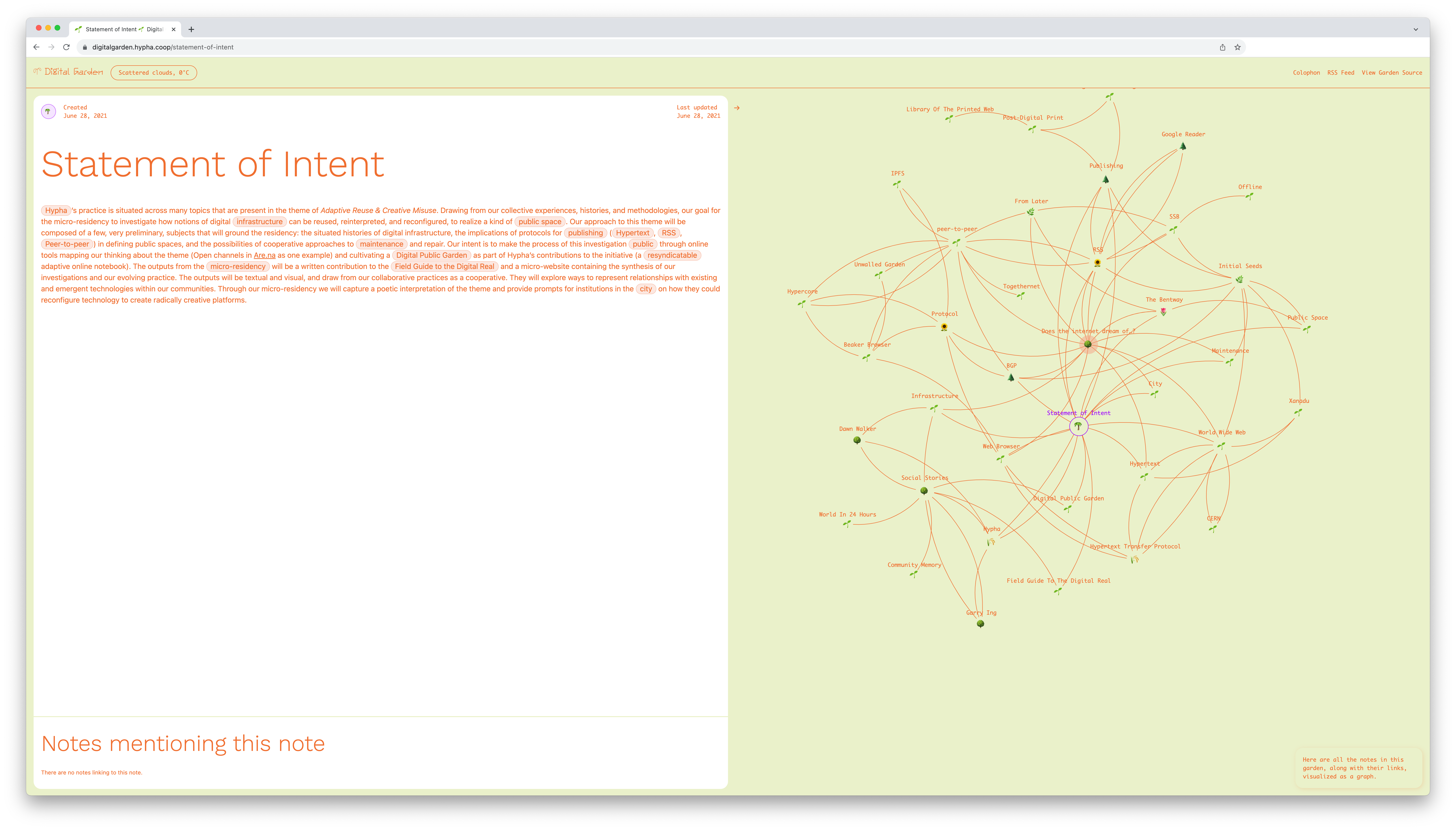

This informs that gathering could remain seen as passive on existing platforms compared to more active processes of journaling or note-taking, recurrent across most of the interviews. Apps such as Apple Notes used by Lucas Erin and Baker Wardlaw, can sometimes bring further context. In a context also marked by the emergence of contemporary productivity software, Gemma Copeland and Baker Wardlaw invested in personal knowledge base (PKB) management systems such as Obsidian (2020) or Roam Research (2019), to build interconnected notes as a digital garden and experiment with a wiki information architecture to enhance associative thinking:

In my personal practice or, as I’m working on Common Knowledge projects, it’s mainly, Are

.na for references and then Obsidian for note-taking, which is also like a digital garden. –Gemma Copeland

In exploring gathering processes on online knowledge networks and user-aggregated platforms, it becomes evident that platforms such as Pinterest, Tumblr, and Are

From passive consumption of context-collapsed content to more active processes of contextualization and gathering through collection-making, curation, notes, blogs, and ultimately networked knowledge of digital gardens, those processes of online gathering and of making sense of their developing visual culture reshape the narrative of individual ownership to the collection, including references as a sum of influences, which creatives could be more public about.

Another question is crucial regarding the collaborative online practice of sharing or not. It is symptomatic of different ways of considering the act of gathering or collection: as a personal process that should be kept behind the scenes, as a personal creative process, or is it considered as part of a community sharing knowledge stance?

Are.na, what type of digital garden?

Defined as an “enclosed area for public entertainment,” the term “Arena”30 not only denotes physical space but also symbolizes a “sphere of interest, activity, or debate”. Within the domain of UGC platforms, data often resides in secluded silos, restricted behind access barriers. Exploring the distinctive realm of collaborative knowledge creation, this chapter unveils the profound impact and intricate design of Are.na —a platform reshaping the landscape of creative processes and information sharing–considered by many as a digital community garden31. While featuring use cases from the interviewees, it is pertinent to note that I am an active member and advocate of this platform.

Are.na : an indie social network for creatives

Are

Described on its landing page as a “more mindful place […] to structure your ideas and build new forms of knowledge together”33, and by members as a “Social media that doesn’t damage your brain”, “Pinterest for nerds” or “A garden of ideas”,34, Are

Instead of being an all-in-one tool that doesn’t do anything well, Are

Channels can either be private, closed (publicly visible, restricted edit) or open (contributable). Asking for a slightly more cognitive load by design, Are

Radically distinctive by its withdrawn minimalist monochromatic design and its default Arial typography, the interface features a calm and distraction-free environment, favoring content over form.

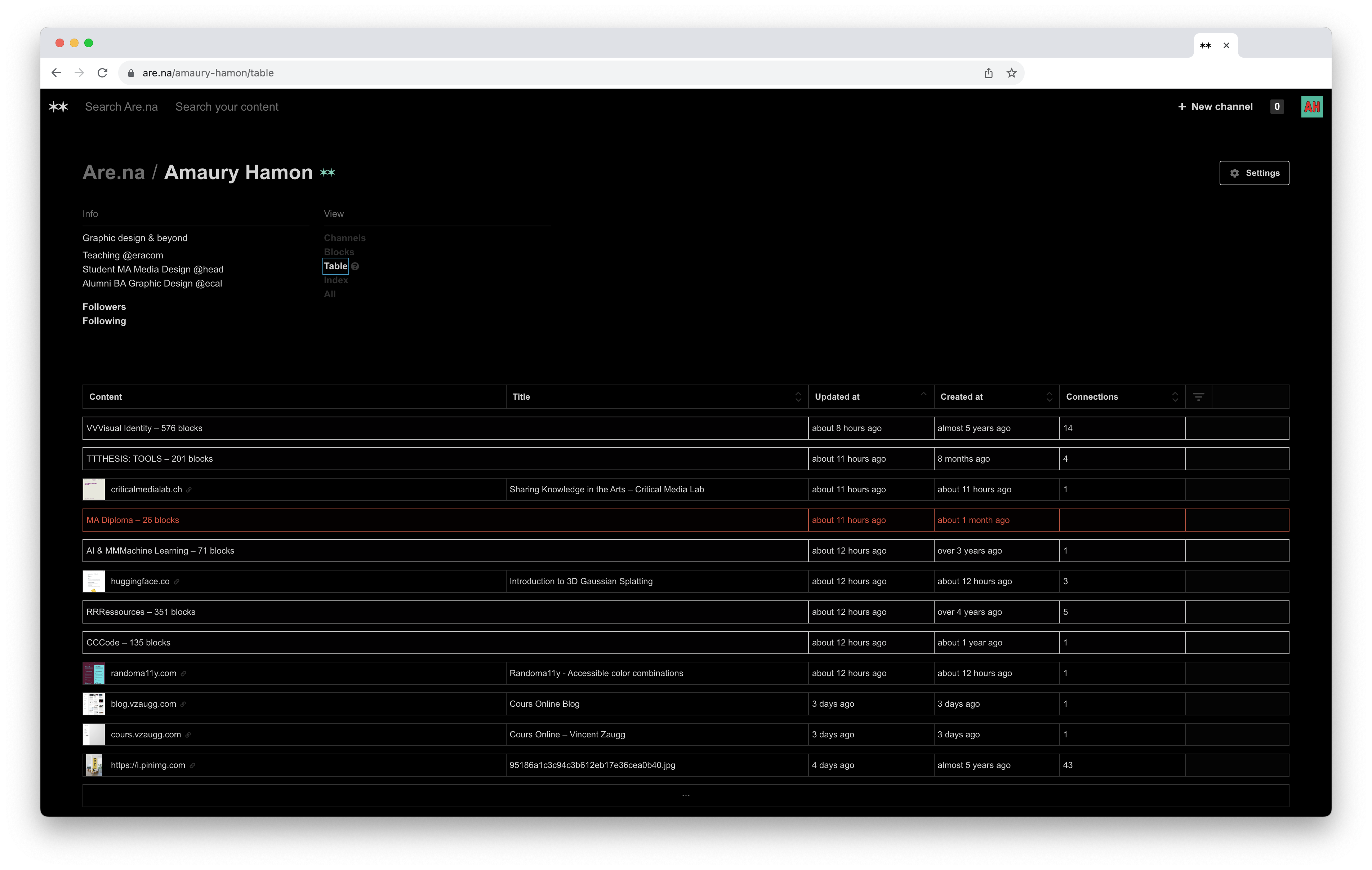

Main pages such as Explore (grid-view) and Feed (stack-view) feature chronologically ordered blocks pooled from either all users or the ones you follow. The Profile and channel pages list content in modular views to choose from (channel rows, blocks only, channels only, table, index).

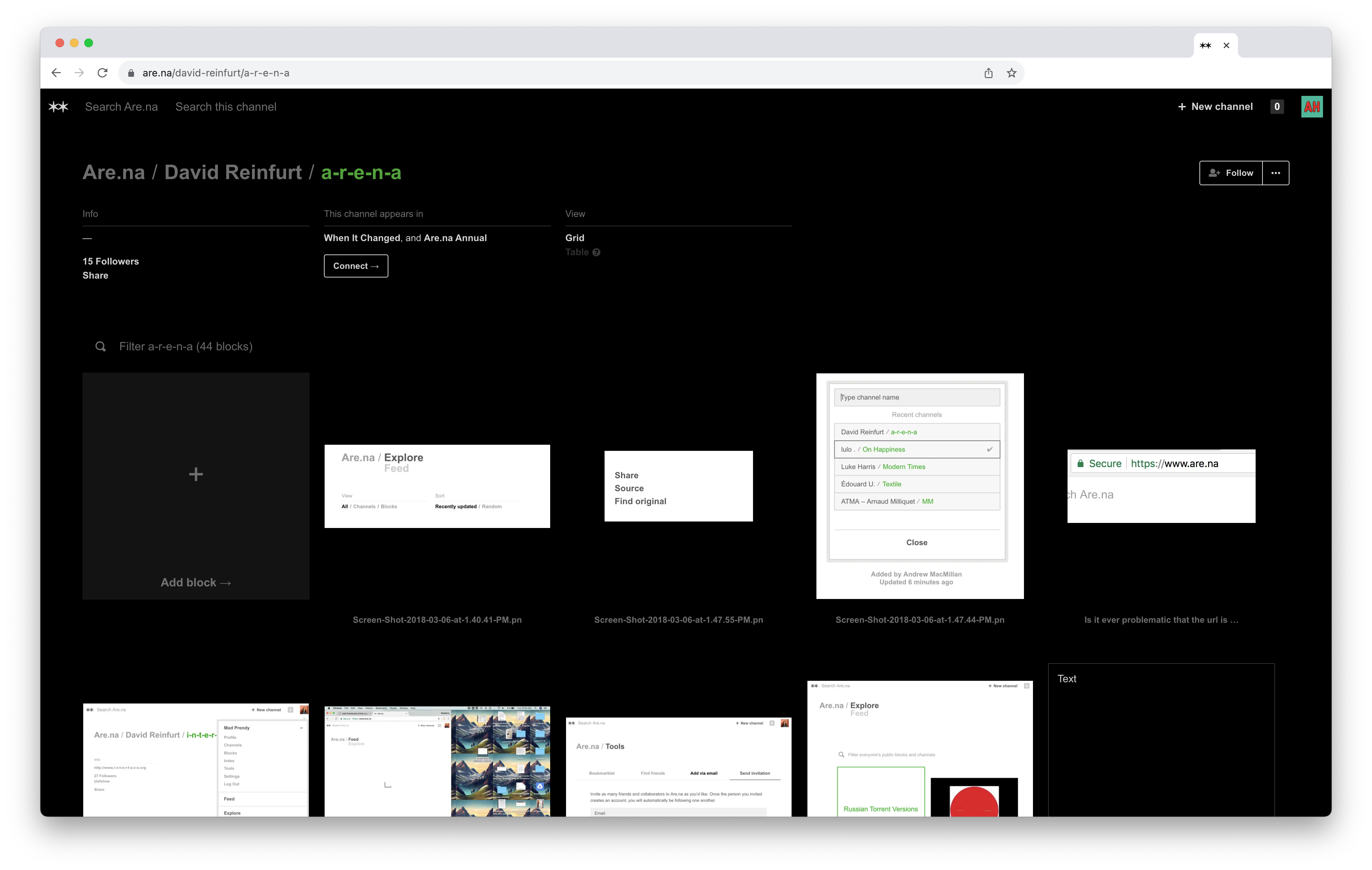

A detailed view of a block showcases all the channels it is branched in, along with metadata (source, connected by and date) and secondary features to comment on. The minimal UI is exhaustively puzzled out as a mise en abyme by David Reinfurt in an open channel a-r-e-n-a.35 According to Daniel, simplicity and reliability are what makes Are

You know why I like to use Are

.na ? Because you can take a hundred images and drag them up on the screen. And it works. You need tools that are stupid simple in the sense that they’re incredibly reliable. –Daniel Robert Prieto

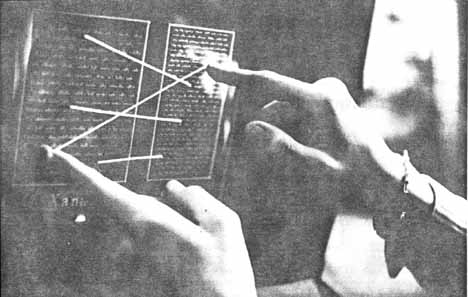

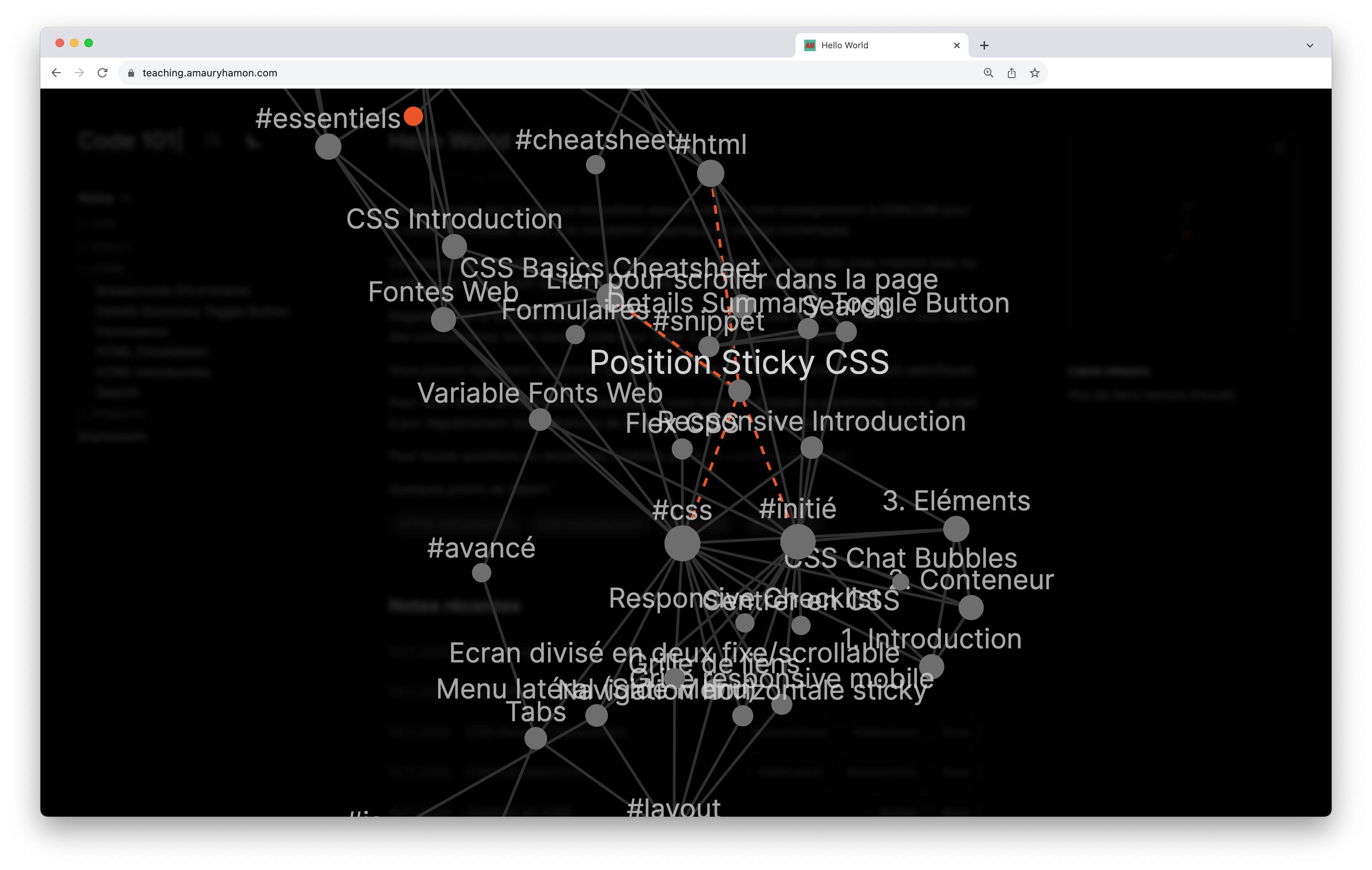

Reminiscent of hypertext Project Xanadu (1960) Project Xanadu, Ted Nelson, 1960., serendipity and networked thoughts are enhanced thanks to the bi-directional linking of blocks & channels. The information architecture is rendered as a folder structure, yet underneath the hood, it works rather as a nodal view. Whether you go single-player or collaborative, blocks and channels are fully interconnected to other members’ channels, proposing a glimpse into the brains of other creatives.

Project Xanadu, Ted Nelson, 1960., serendipity and networked thoughts are enhanced thanks to the bi-directional linking of blocks & channels. The information architecture is rendered as a folder structure, yet underneath the hood, it works rather as a nodal view. Whether you go single-player or collaborative, blocks and channels are fully interconnected to other members’ channels, proposing a glimpse into the brains of other creatives.

Open Source by default while remaining private, Are

Metrics set the platform as quite a niche compared to bigger mainstream platforms. Currently composed of 27391 monthly active members, 13617 of them are paying members, and the platform generates 1.21 million monthly connections. Its self-sustainability model currently generates a monthly revenue of $80841, allowing for the maintenance costs, and remuneration of the small team in charge of full-time and part-time positions in engineering, product and operations, editorial events, and merchandising. This smaller scale factor allows its dedicated members to sense better ownership (through feedback channels, community events, and publications).

Use cases from interviews

Being an open-ended platform, Are

It’s pretty hard to know what the real purpose of the people who created these platforms is, I’ve never looked. There must be instructions for use, I don’t know. I’ve never thought about it. I just intuitively did what was most useful for me. –Aurélie Vial

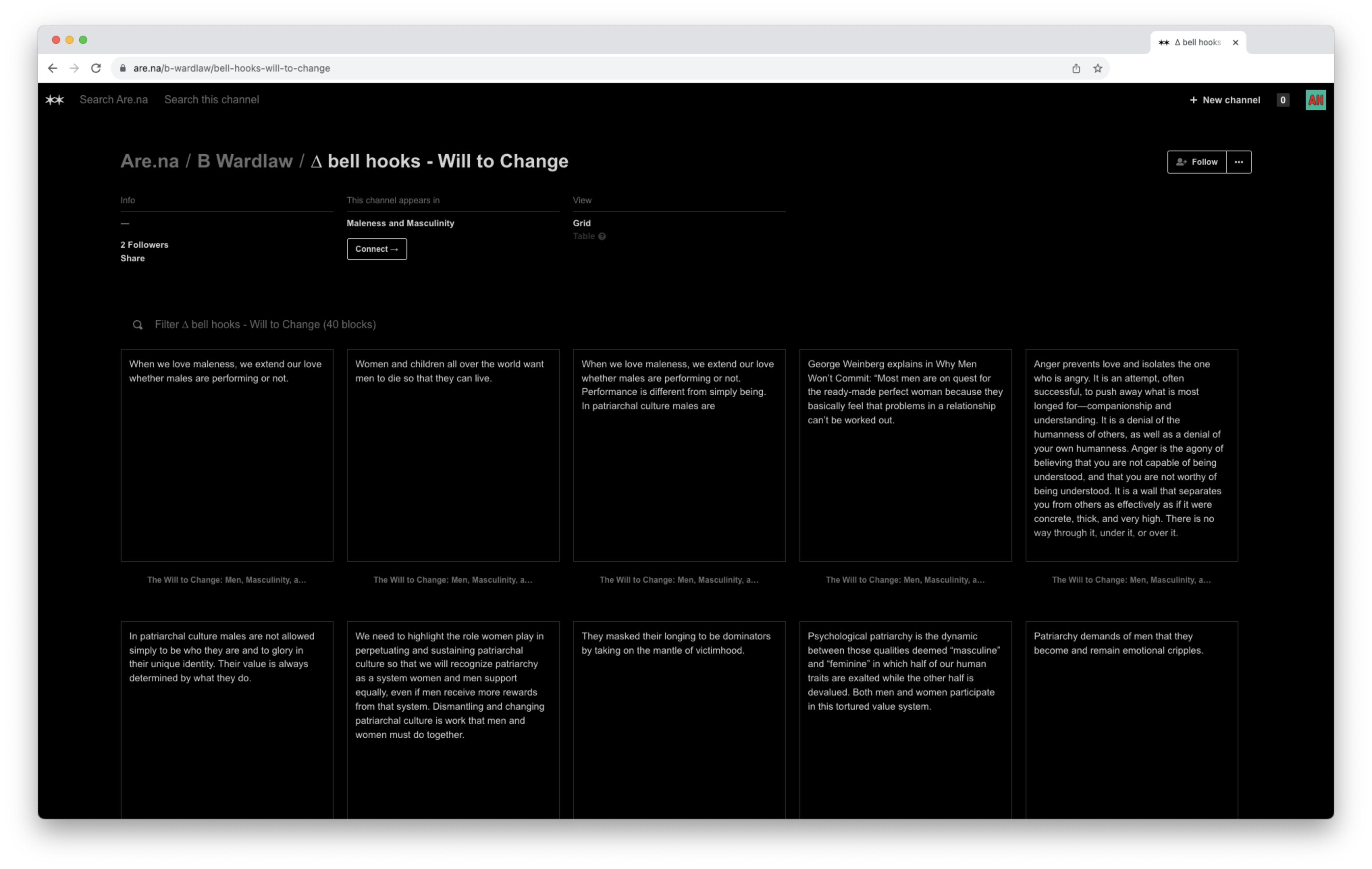

The interviews drew a diverse range of use cases about interviewees’ gathering methods and creative research purposes. Florian creates private channels to stimulate the birth of a project while creating public channels on the side for more general mood boards.41 Most of Baker’s and Gemma’s are open channels, encouraging other members to contribute elements. Aurélie creates private collaborative channels teamwork mood boards which she can then share with her clients, stating: “I don’t just take blocks, part of what I add is images I’ve taken from sites, from Google, from Pinterest. But I also, scan things from books or other sources and add them to Are

I wouldn’t say that I hack Are

.na , but I would say that I have a fairly conventional use of a tool that’s relatively unconventional in the sense that the first time you show it to people, they are like “What’s this thing?” –Baker Wardlaw

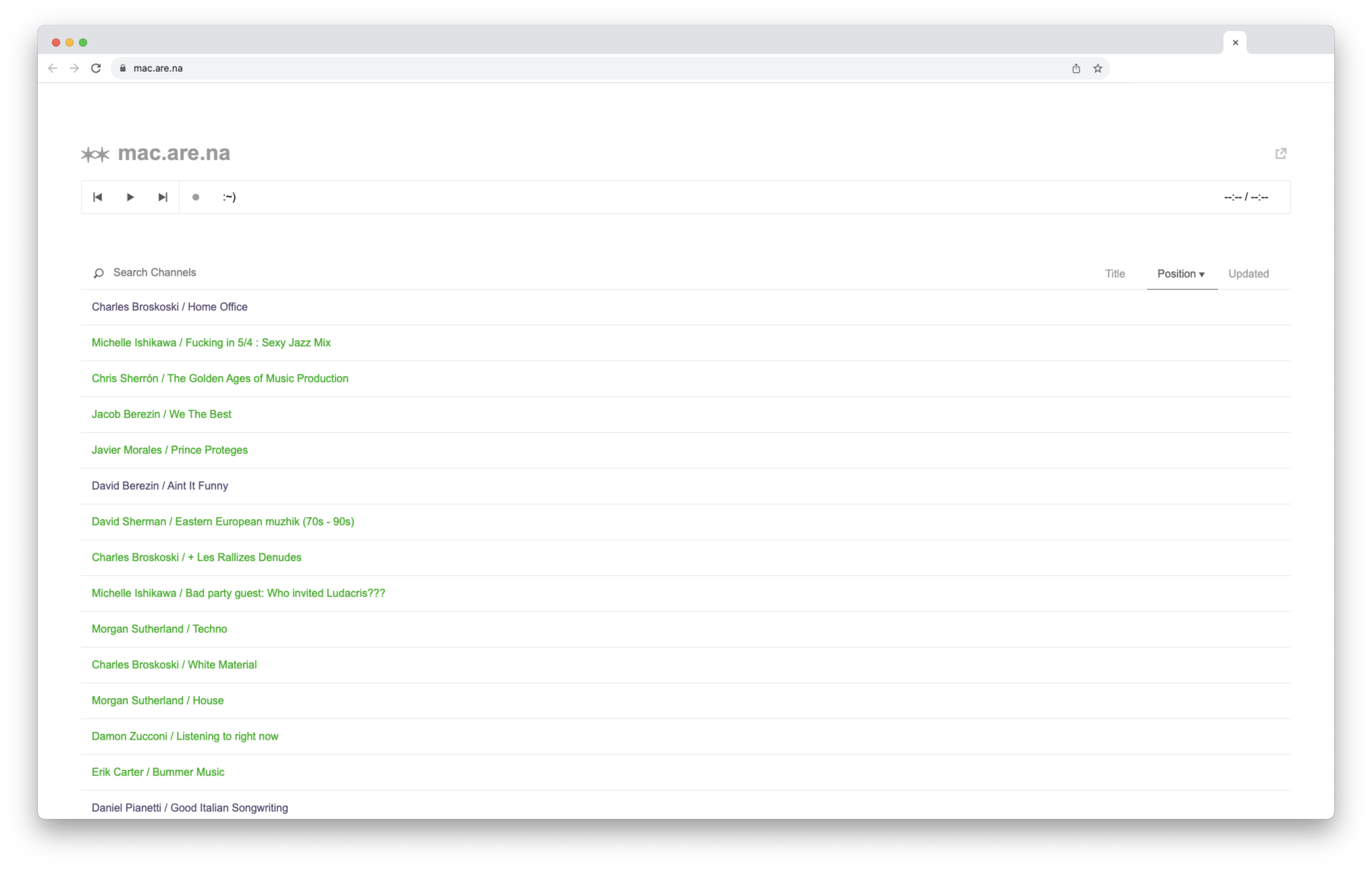

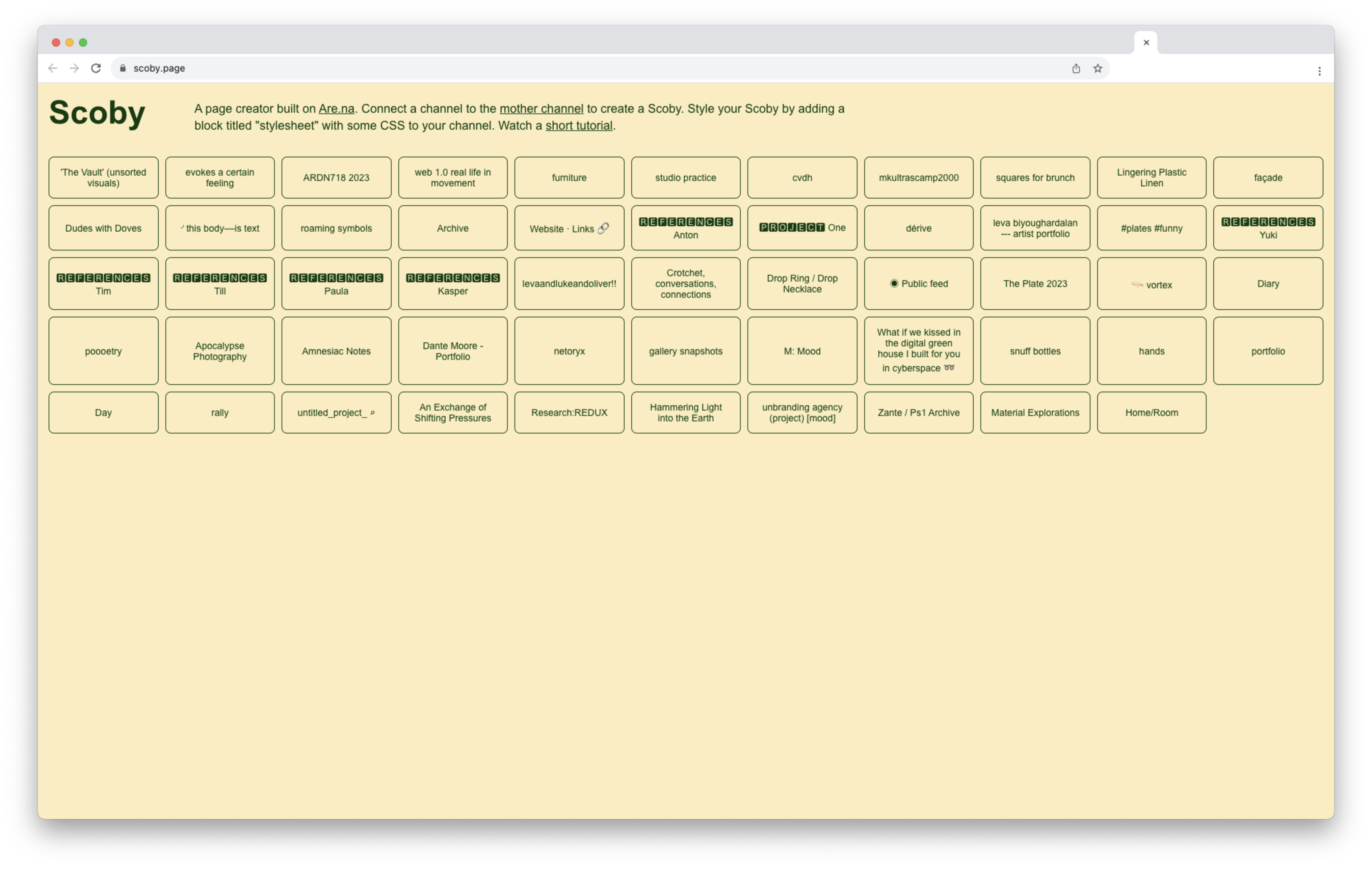

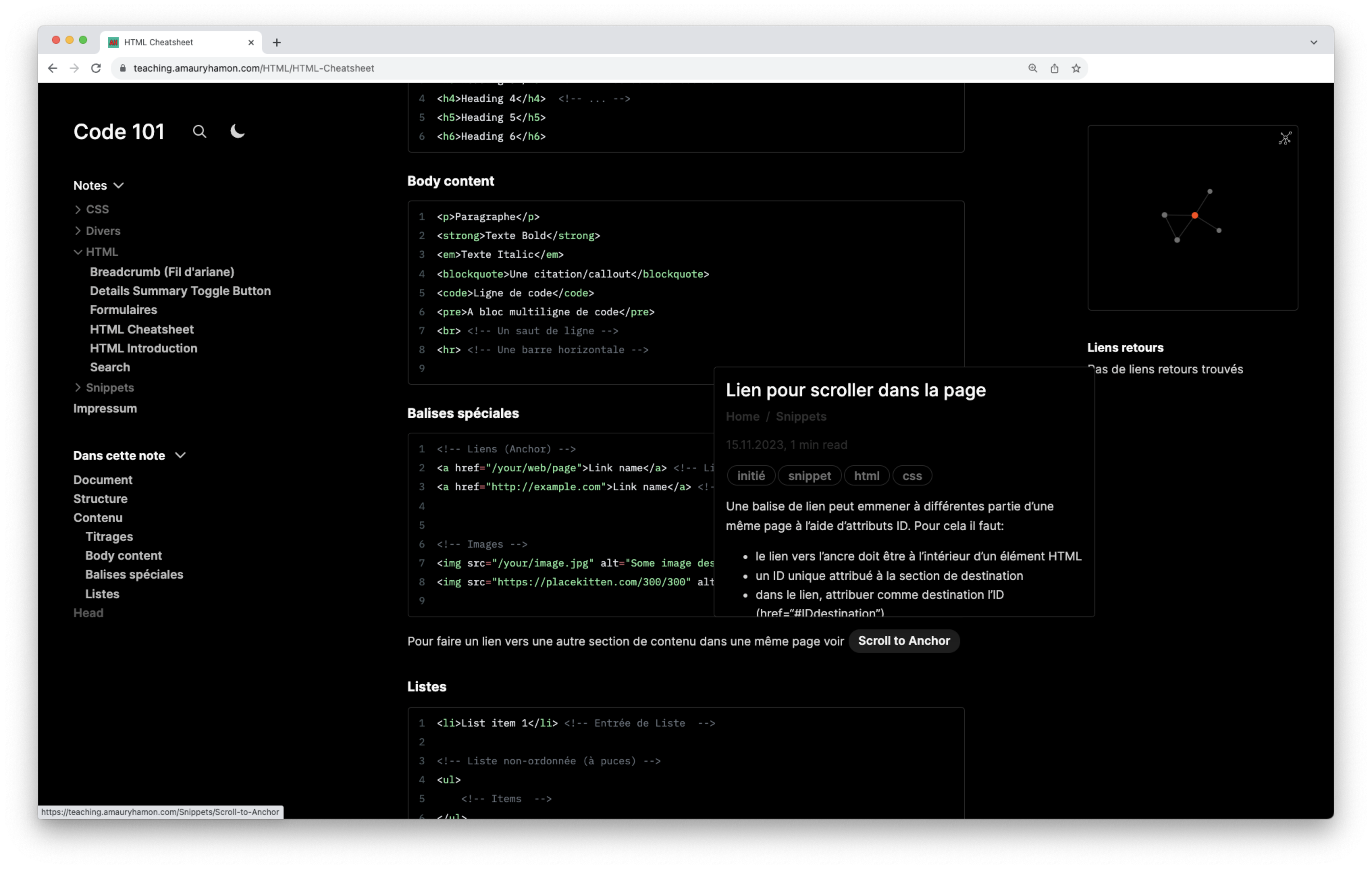

Advanced use cases, such as the use of Are

Jonas created an online web design gallery connected to one of his channels.44 As Jonas says: “I was collecting inspiring website designs for myself for two years already when I started playing around with the API and built this site. What was originally intended as a fun little experiment has now turned into quite a popular design showcase.” Similarly, Baker Wardlaw and the teaching staff of a visual arts course for architecture students at EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) created an Are

Open-endedness Versus Limits of a Platform Impacting Creativity

From those interviews, three profiles were drawn: from fully private profiles to mixed feelings between sharing and gatekeeping specific channels, and to fully displaying publicly or allowing contribution to the channels.

They helped me draw out a tension point on originality and singularity of research compromised by a personal curation process within uniformized collective gatherings of inputs, or social bubbles.

Depending on who you follow and how many, Frederik draws parallels between Are

Passively scrolling through the content on Are

As Charles Broskoski stated in his 2019 conference, “The more you use Are

Frequency of use is one identified tension point drawn from interviews, leading to both benefits of enhanced access to references and gathering, yet inconveniences of death-scrolling expressed by Frederik or Aurélie, or social bubbles of homogenized references according to him and Émilie.

Frederik argues: “The people I follow on Are

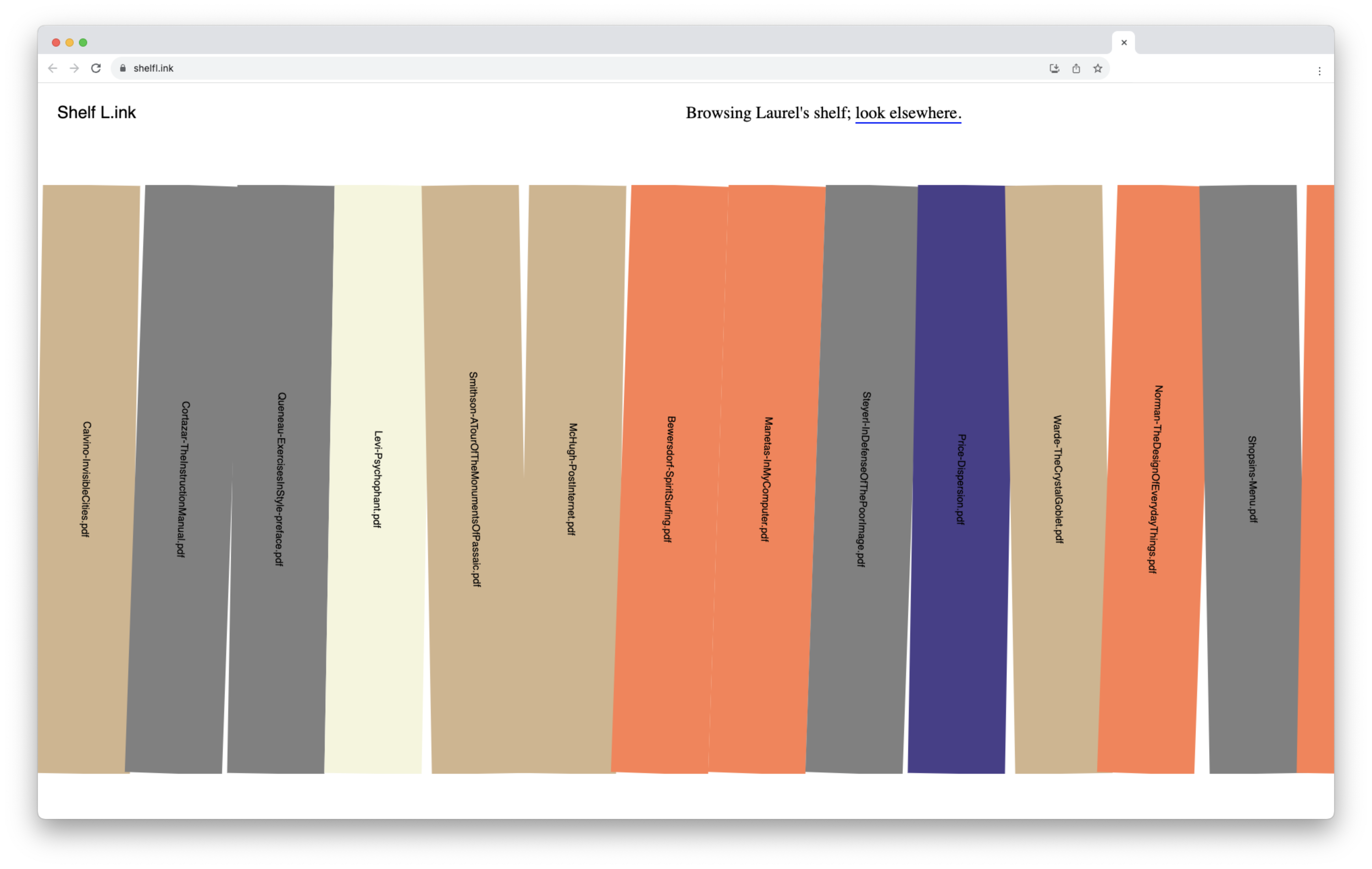

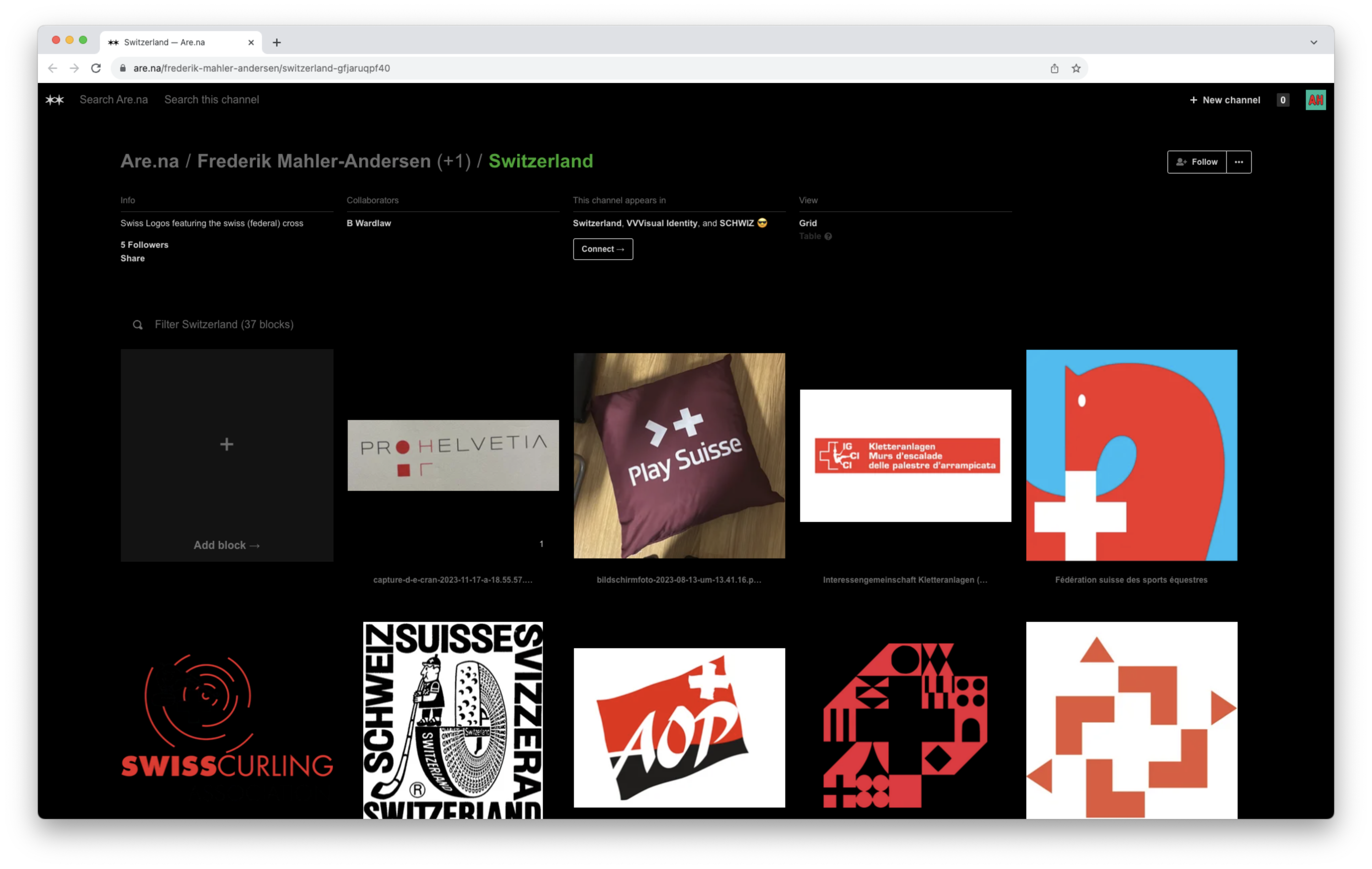

While Frederik remains partly open to sharing on a restrictive basis, he likes for some “to keep them public. I have this channel of Swiss logos48 that I find quite funny, it’s even open to contribute”. His private channels need to be reviewed first before sharing, which he prioritizes in-real-life situations.

Daniel tests the quantitative success of a curated channel by waiting to gather sufficient content before it becomes a thing ready to publish: “If that river goes nowhere, it just dissolves. So then what I do with these things is keep them private.” For Jonas, his channels are rarely open for contribution, only his “more general research ([…] graphic design or useful development resources) is public from the start. Project-specific research often starts private and is sometimes published later.” He also had similar concerns to Frederik, about the potential lack of context in sharing project-specific research.

The collaboration and contribution to channels are quite disparate from the results of the interviews. Baker and Gemma, on the other hand, are fervent members of the “Go Green” open channels, embracing contribution and the social network aspects of Are

Having the channels open, was a decision I made a few years ago, in this idea of not trying to gatekeep or say “these things are my own” because, at the end of the day, it’s a collection of other people’s things. So why should I be “this is mine as the curator.” –Gemma Copeland

In her gathering process, Gemma states green channels as means of honesty in her research, and she always tries to look for existing open channels first before creating her own:

If I’m working on something and I want to keep the channel private, then it’s also an interesting prompt for me to understand why, is it that I’m taking too much reference from these things and perhaps it would be better to make it open and make sure that you’re not like secretly being derivative. I feel the public-private thing is interesting because it’s also about honesty or making sure that you’re not ripping people off or getting too influenced by things. “These are my deep cut, private references. That’s my secret sauce for how I do cool design.” –Gemma Copeland

Are.na , a Digital Garden in the Cozy Web?

This concluding part ventures into the similarities shared by

Are

Caulfield’s understanding of digital gardens earlier introduced, implies gardening is not about using specific technologies but rather how to rethink our online behavior towards information, through personal and explorable online space. As our Web navigation progressively delved into streams of collapsed information into single-track timelines of events–from social media feeds and chats–the lifespan of information is limited and not designed to be accumulated and grow over time as implies Gemma Copeland:

It’s about not trying to use things that are always distracting you and also building that collective knowledge base over time. WhatsApp or Slack, everything gets lost in the stream. You’re not building anything long-term, you’re just chatting and it’s chaotic. –Gemma Copeland

Through its introverted interactions and interconnected architecture, Are

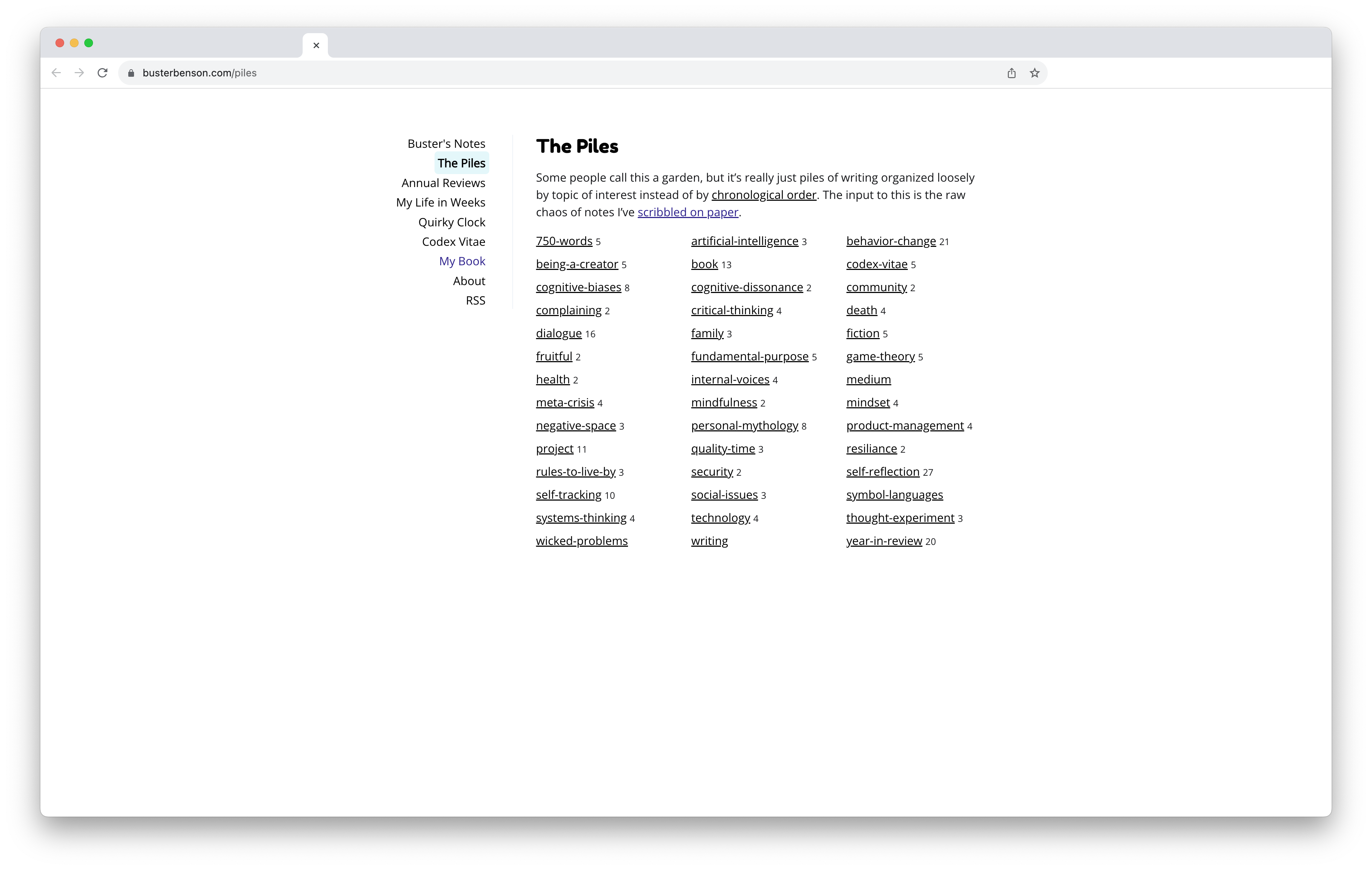

Digital gardens: not just a blog

Digital gardens, unlike traditional blogs and platform feeds, eschew the chronological or algorithmic confines of a timeline and instead, emphasize manual contextual relationships and associative links, similar to Are

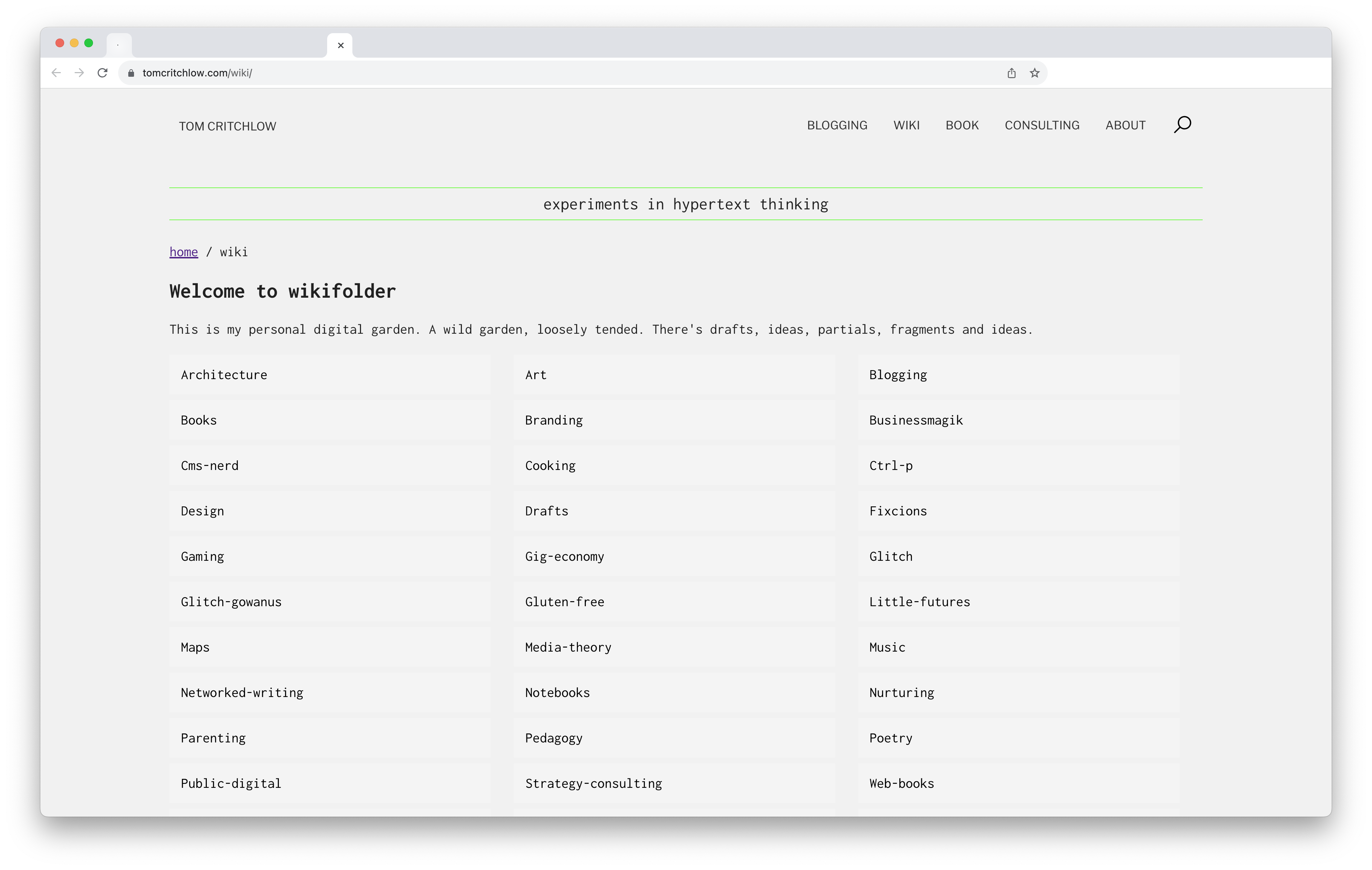

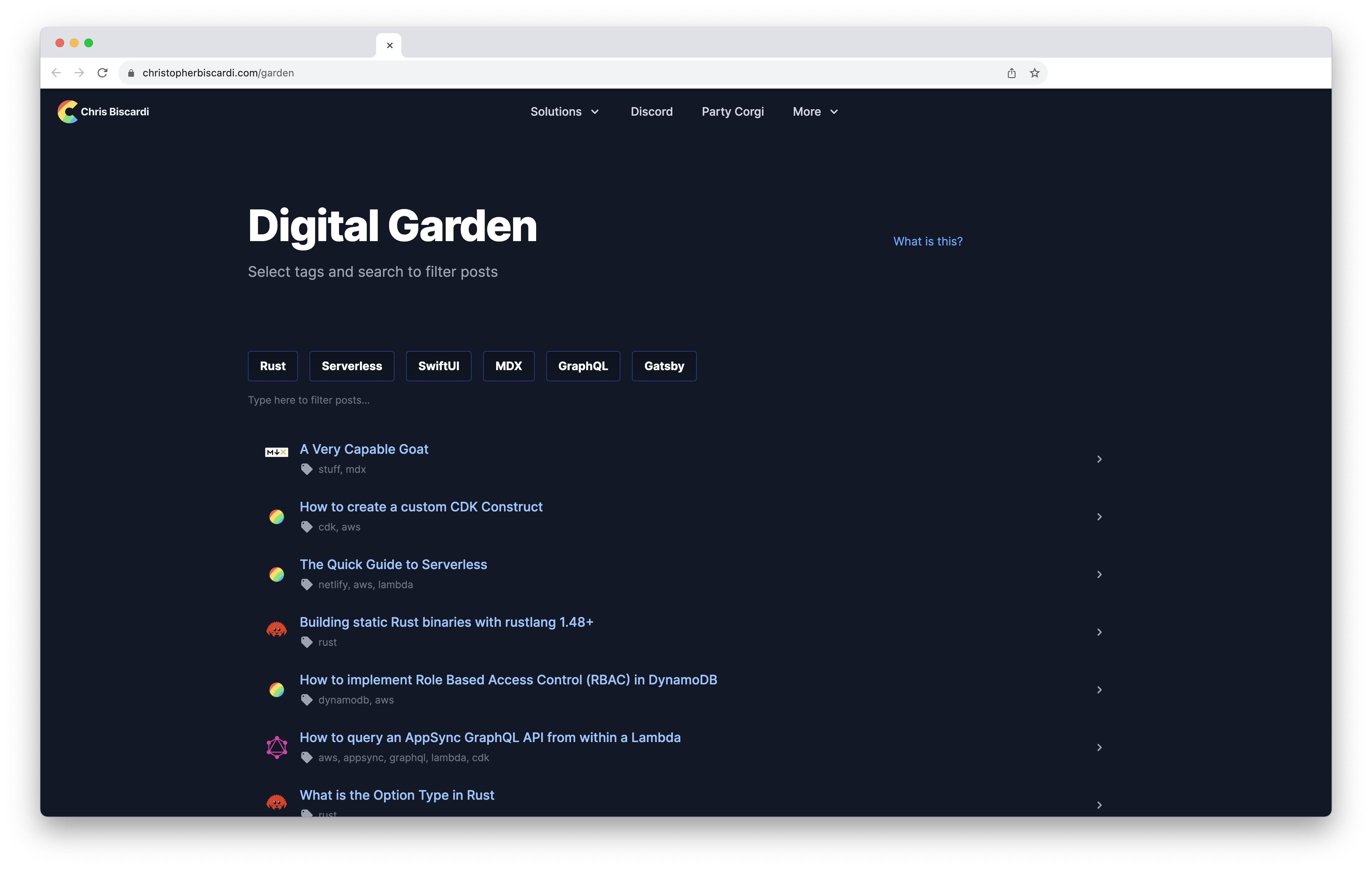

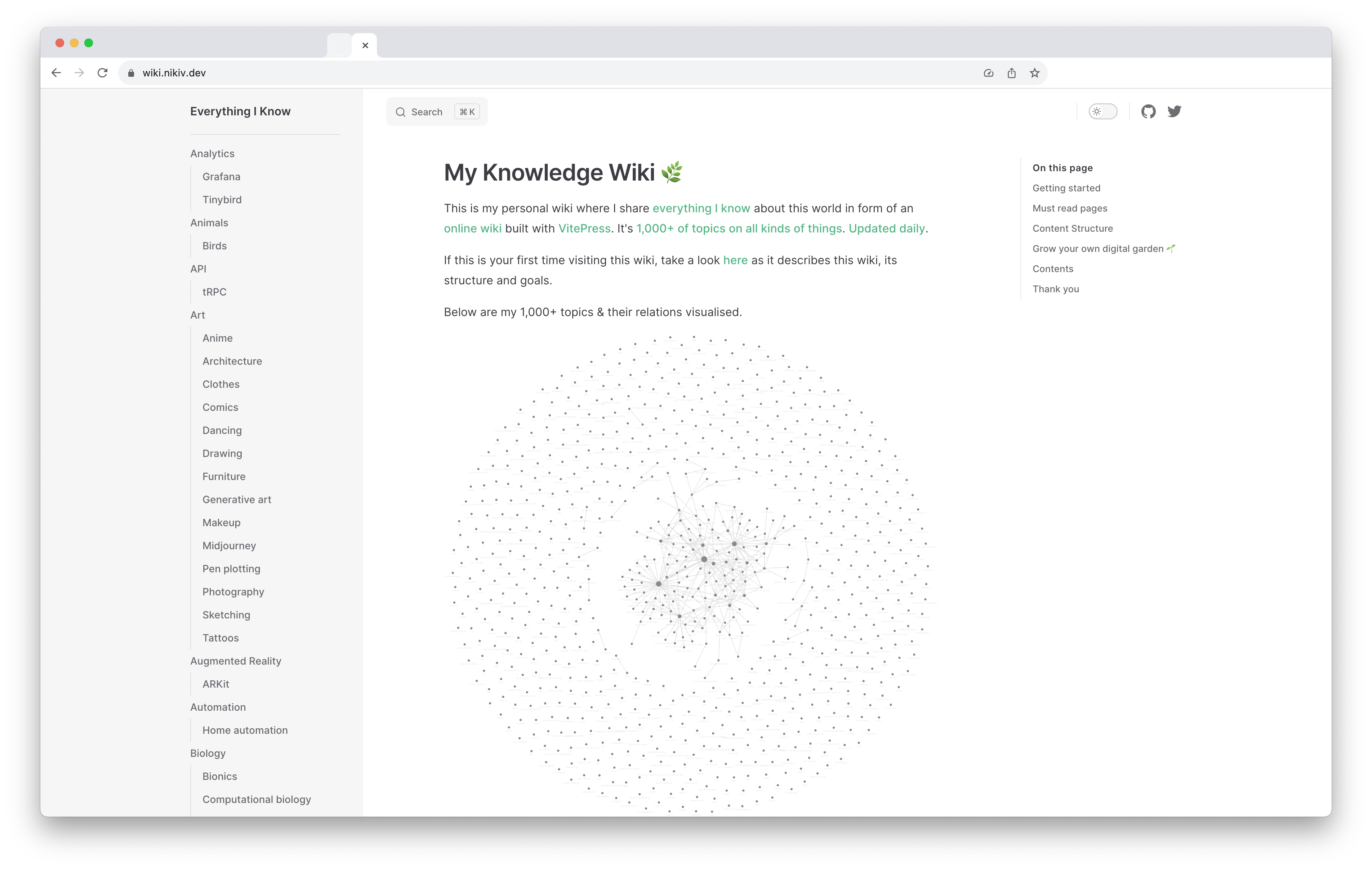

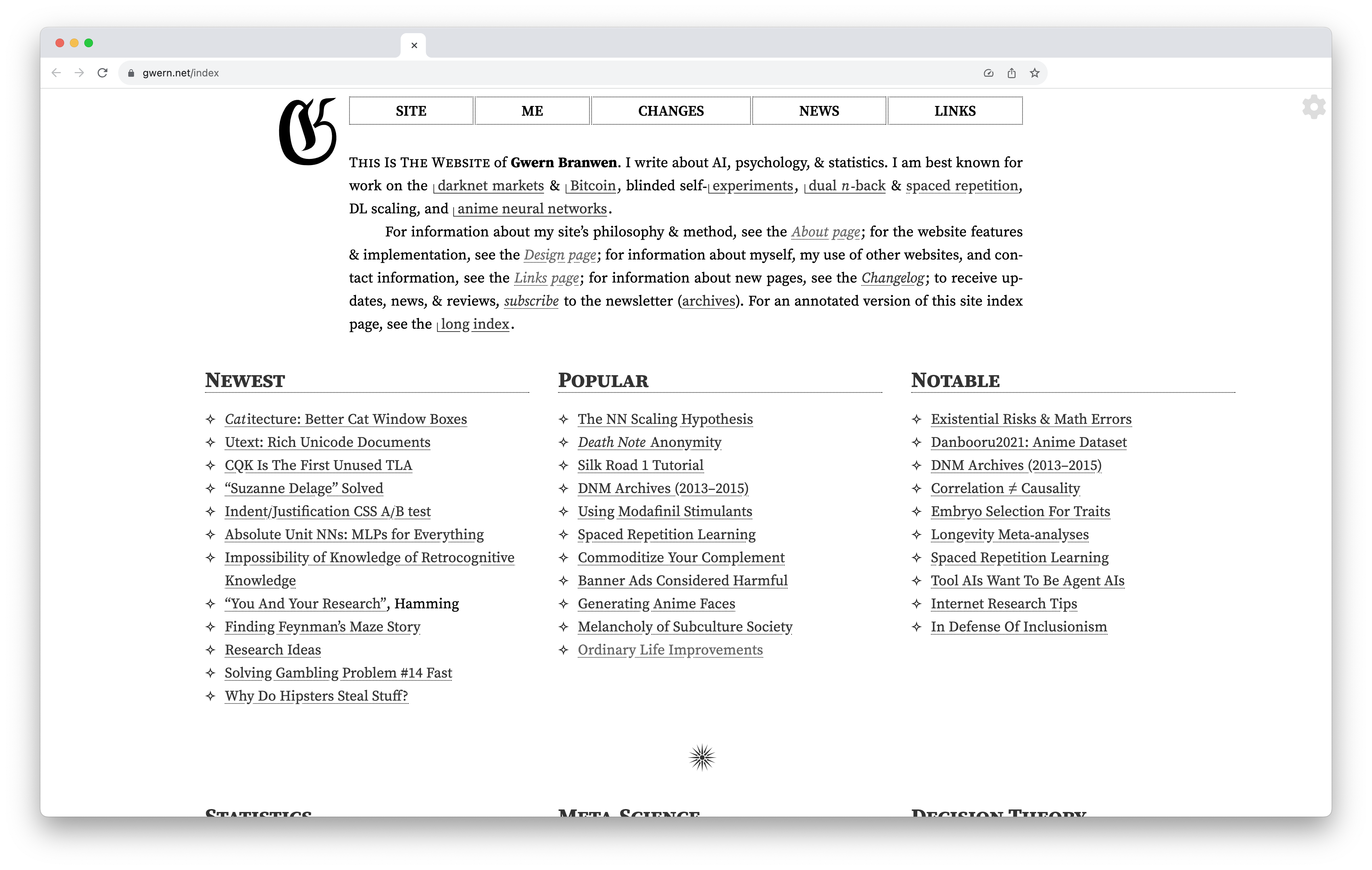

This topology over a timeline allows digital garden readers to traverse content via bi-directional linking, thematic piles52, nested folders53, tags54, advanced search bars, and visual node graphs55, creating a non-linear, explorative experience, while questioning the established norms of a personal website playfully. While Are

bi-directional linking and nesting channels in others certainly reflects this nonlinear exploration.

Continuous growth is fundamental to digital gardens, and

Are

The essence of learning in public is central to digital gardening, encouraging sharing and learning during the learning process, not as an expert or individual genius retrospectively, which Are

These gardens challenge the norms of personal websites, aiming for deep contextualization amidst the chaos of the internet, for which Are

Independently owning a digital garden is pivotal and radical; it ensures control and ownership, diverging from cozy walled gardens and platforms like Facebook or Twitter. None of these platforms are designed to help you slowly build and weave personal knowledge. Except for Are

Additionally, as Daniel states, “[platforms] come and go, no matter how powerful or stable they seem to be”, your writing and creations can sink with it. Almost none of them have an easy export button. And they certainly will not hand you your data in a transferable format. This reflects the topics of Data and Privacy Concerns within Antitrust Laws about considerations of how dominant tech platforms handle user data. This involves examining whether the collection and use of data create unfair competitive advantages or harm consumer privacy.

While digital gardens currently end up being solitary endeavors, efforts are underway to create multiplayer spaces, which Are

In essence, digital gardens symbolize a shift towards a more intentional, less performative, yet engaging and personalized approach to sharing knowledge. They encapsulate the dichotomy between chaos and cultivation, embracing imperfection, continuous growth, and responsible sharing in a multimedia-rich, non-linear environment—all while securing ownership and control within the vast expanse of the internet. Are

Conclusion

In conclusion, the exploration of how creatives gather and share resources within the broader landscape of private aggregated UGCCCC platforms, with Are

Interviews with creatives shed light on a plurality of methods and approaches on used platforms, from gatekeeping to radical active ways of gathering and sharing, influencing in turn the overall practice of creatives. The beneficial enhanced access to inspiration with widespread visual culture leads simultaneously to context concerns, which depending on passive or more active methods, leads to either decontextualization, homogenization of visual culture, or deep contextualization. The balance between radical shared ownership of gathering and public sharing while preserving the intimacy of one’s research emerged as a significant challenge, with diverse perspectives on the economic value of creative endeavors online in a market driven by competition. Gatekeeping, by nurturing scarcity instead of abundance models, tended through public curating, contributing, and sharing resources. This collaborative commoning approach to gathering and sharing is critical to pivoting default competition on originality into better collaboration and engagement with the creative community.

Through its steady growth, Are

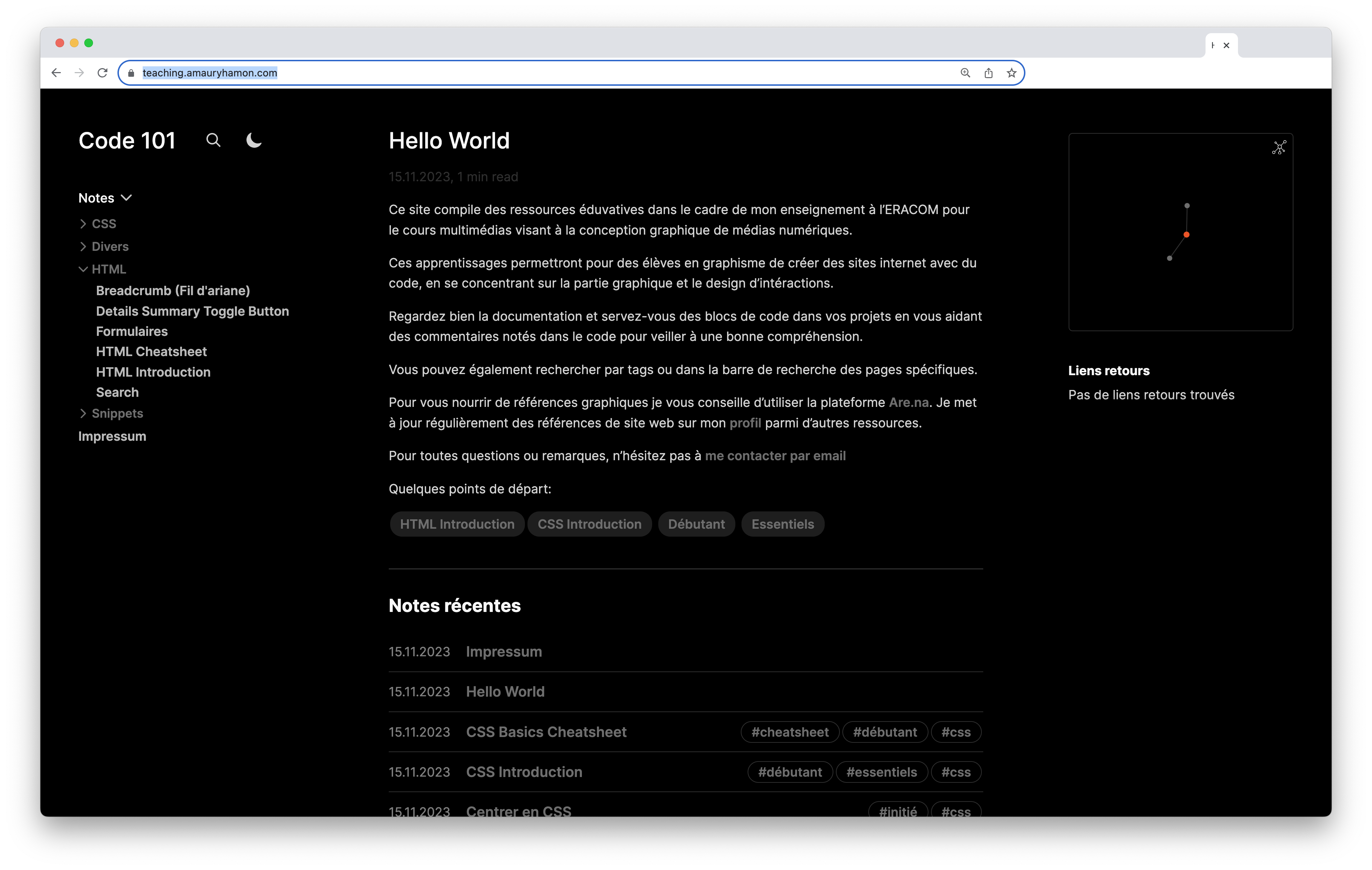

Simultaneously to the writing of this thesis, to better understand the possibilities of digital gardening, and what were the possibilities and the limits of UGCCCC / Are

Design Notes

My MA Thesis was initially designed as a website, utilizing Paged.js and PageTypeToPrint to explore the concept of single-source publishing. This approach aims to centralize content management, minimizing errors, and leveraging web technologies to present content across various media formats.

The website is adaptable for printing in pocket book format (Work in Progress) and universal A4, catering to anyone with a printer. For accessibility, the web-based content integrates multimedia elements such as video, audio recordings from interviews, textual transcripts, and visual content.

Additionally, this project serves as a personal experiment with alternative publishing and writing tools, diverging from standard corporate options. With a background in printed graphic design, my professional goal is to merge design with coding, moving towards a hybrid model of design and computation. I also prioritize supporting libre, open-source, and community-driven alternatives like collaborative writing pads and the paged.js library.

By harnessing web technologies like HTML’s semantic markup, CSS for visual styling, and the functionalities of JS and PHP, Paged.js facilitated the production of both the website and its printed document in multiple formats.

The design of this web thesis emerged serendipitously while exploring GitHub repositories for web-to-print resources. I stumbled upon PageTypeToPrint, a template developed by Julien Bidoret for ESAD Pyrénées School of Art & Design Master Thesis writings. I’m grateful for this open-source tool, which provided a foundation for the coding architecture. It allowed me to customize the design and functionalities according to my thesis needs, despite my initial limited coding skills—skills that have hopefully improved throughout this multimedia journey. The following screenshots offers a preview of the overall workflow.

Glossary

- API (Application Programming Interface)

- is a set of protocols, tools, definitions, and functionalities that enable different software applications or systems to communicate and interact with each other. It defines how different software components should interact, making it easier to integrate and access data or services from one to another.

- Attention Economy

- refers to the economic system in which attention becomes a scarce and valuable resource. In this system, companies compete for individuals’ attention through various platforms and services, often relying on techniques like targeted advertising and addictive design to capture and hold attention for financial gain.

- Collection

- refers to a grouping or assembly of items, objects, or entities that share common characteristics or are gathered for a specific purpose. Collections can vary widely in their nature and can include physical objects, digital items, data sets, or abstract concepts such as groups of related ideas, concepts, or theories gathered together for a specific purpose. The term “collection” implies a deliberate act of gathering or organizing items together based on certain criteria or for a specific reason. Collections often serve as valuable resources for study, research, enjoyment, or reference, providing a curated set of items that share common attributes or themes.

- Context Collapse

- refers to a phenomenon in social media or online communication where different social contexts or audiences merge into one, causing challenges in managing privacy, self-presentation, and communication styles. It occurs when content intended for a specific audience or context is shared widely or made accessible to diverse groups, blurring the boundaries between social spheres.

- Creativity

- is the ability to generate original ideas, concepts, or solutions that are novel, valuable, and relevant in a particular context. It involves the process of thinking divergently, exploring new possibilities, and producing something unique by combining existing elements in innovative ways. Creativity often involves connecting unrelated or disparate concepts, ideas, or elements to generate innovative outcomes or insights. The creative process involves different stages, including preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification, although these stages can vary based on individual approaches and the nature of the creative task.

- Curation

- refers to the process of selecting, organizing, and presenting content, items, or information in a thoughtful and deliberate manner to achieve a specific purpose or goal. It involves sorting through available material, choosing the most relevant or valuable pieces, and arranging them in a meaningful way. In the digital realm, content curation involves gathering, organizing, and presenting digital content (such as articles, videos, images, etc.) from various sources on a specific topic or interest. Content curators often compile and share such collections through blogs, social media, or platforms.

- Death-Scrolling (or Doomscrolling)

- is a term used to describe the act of continuously scrolling through social media feeds, websites, or digital content for an extended period, often to the point of exhaustion or mental fatigue. This behavior can lead to spending excessive time consuming online content, resulting in negative effects on mental health, productivity, and well-being.

- Digital Garden

- is an evolving collection of ideas, notes, and resources interconnected that are organized and shared online. It serves as a platform for personal knowledge management and allows for non-linear exploration and collaboration.

- Gatekeeping

- refers to the practice of controlling, filtering, or regulating access to information, opportunities, resources, or communities by individuals or groups in a position of authority or influence. It involves determining what content, individuals, or ideas are allowed to pass through a particular gate or barrier, thereby influencing who gains entry or recognition within a specific field, industry, or community.

- Gathering

- refers to the act of assembling or collecting things, people, information, or resources together in one place or for a particular purpose. It involves bringing together various elements or individuals to form a group, collection, or assembly. With the advent of digital platforms, gathering can also take place virtually or online, where people come together through video calls, webinars, online forums, or social media platforms to share information, ideas, or engage in discussions, aimed at creating connections, sharing resources, or achieving common goals.

- Knowledge

- refers to the understanding, information, skills, and awareness acquired through learning, experience, study, or discovery. It encompasses facts, insights, principles, beliefs, and concepts that an individual possesses and can apply or use in various contexts.

- Knowledge commoning

- refers to the practice of collectively creating, sharing, and stewarding knowledge as a commons. It involves the collaborative and community-driven effort to generate and maintain a shared pool of knowledge resources, often through open and participatory processes that prioritize accessibility and collective ownership.

- Sharing

- refers to the act of giving, contributing, or distributing something with others, whether it’s tangible items, resources, information, experiences, emotions, or ideas. It involves offering a portion of what one possesses or knows for the benefit or enjoyment of others. Sharing information involves disseminating knowledge, data, facts, or insights with others. It can occur through various mediums, such as digital platforms. In collaborative efforts, sharing refers to teamwork or joint contributions toward a common goal, where individuals pool their resources, skills, or efforts for mutual benefit. With the rise of the internet and social media, sharing has expanded to digital realms, where individuals share content, photos, videos, opinions, or thoughts through online platforms for others to see, engage with, or learn from. Sharing is often seen as a fundamental aspect of social interaction and cooperation. It fosters connections, builds relationships, promotes empathy, and allows individuals to contribute to the well-being of others. The act of sharing can bring about a sense of community, generosity, and mutual support among individuals or groups.

- Social Media Fatigue

- refers to a state of mental exhaustion, burnout, or reduced interest experienced by individuals due to prolonged or excessive use of social media platforms. It’s characterized by feelings of overwhelm, disengagement, or dissatisfaction with the time spent on social media networks.

- Post-Capital

- refers to a theoretical framework that envisions a future beyond the capitalist economic system. It explores alternative models that prioritize sustainability, social justice, and collective well-being, aiming to address the inherent flaws and inequalities of capitalism.

- Public Learning (Learning in Public)

- refers to the process of acquiring knowledge and skills through open and inclusive educational practices that are accessible to a wider community. It emphasizes collaboration, shared resources, and collective participation to foster lifelong learning and empower individuals in a public setting.

- Surveillance Capitalism

- refers to the economic system where companies profit by collecting and analyzing massive amounts of personal data from individuals for targeted advertising and behavioral manipulation. It involves the exploitation of digital surveillance technologies to commodify and monetize people’s private information.

- User-Generated Content Platform

- is an online service or platform where users can create, share, and interact with content, typically in the form of text, images, videos, reviews, comments, or other media. These platforms enable individuals to contribute their own content, which is then accessible to a broader audience. Examples of UGC platforms include social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and YouTube, where users can upload and share their own content with followers or the public. Additionally, forums, discussion boards, blogging sites, and certain apps focused on content creation and sharing fall under the UGC platform category.

References

Bibliography

LAWSON, Mark,

Berners-Lee on the read/write web, BBC News [online], 9 August 2005, http:

STATCOUNTER GLOBALSTATS, Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet Market Share Worldwide, Statcounter GlobalStats [online chart], September 2023,

https:

[consulted: 16 October 2023]

LIALINA, Olia et al. (eds.), 2009. Digital Folklore: to computer users, with love and respect. Stuttgart: merz & solitude. Projektiv. ISBN 978–3–937982–25–0. [online]

https:

ERTZSCHEID Olivier, 2013,

Qu’est-ce que l’identité numérique? Enjeux, outils, méthodologies, Marseille, OpenEdition Press, series: « Encyclopédie numérique », 69 p.,

ISBN 978–2–8218–1337–3.

KRIM, Tariq, 2023, Slow Web [online] https:

ODELL, Jenny, 2019.

How to do nothing: resisting the attention economy. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

ISBN 978–1–61219–750–0.

BROSKOSKI, Charles, 2019. Creating the new social web,

The Conference [online]. Malmö, Sweden. 28 August 2019. Retrieved from: https:

LOVINK, Geert, 2021,

Notes on the platform condition,

Making and Breaking. [online] https:

BEYENS, Ine et al., 2020.

The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Scientific Reports.

Vol. 10, no.1, p. 10763.

DOI 10

MERRIAM WEBSTER,

Definition Garden, [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.27]

R. CARPENTER, J., 2015,

A Handmade Web, LuckySoap. [online] http:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

BERNSTEIN, Mark, 1998.

Hypertext Gardens [online]

http:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

CAULFIELD, Mike, 2015,

The Garden and the Stream, a Technopastoral, HapGood, [online] https:

[consulted: 2023.11.27]

NOVA, Nicolas, 2021. Enquête/Création en design. Genève: HEAD Publishing. Manifestes, 2.

ISBN 978–2–940510–47–4.

HAMON, Amaury, 2023.

TTTHESIS: TOOLS, Are

[consulted 2023.11.25].

LE GUIN, Ursula K., YI, Pul and HARAWAY, Donna, 2019.

The carrier bag theory of fiction. London: Ignota.

ISBN 978–1–9996759–9–8.

SEU, Mindy, 2021.

On Gathering. Shift Space [online].

No.1. https:

HAMON, Amaury,

Timeline of technologies and services for online creative research (1963–2023), [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.27]

MERRIAM WEBSTER,

Collection definition, Merriam Webster Dictionary, 2023, [online] https:

OBRIST, Hans Ulrich, 2014.

Ways of curating. First American edition. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc. ISBN 978–0–86547–819–0.

CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, Mihaly, 2013. Creativity: the psychology of discovery and invention. First Harper Perennial modern classics edition. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

ISBN 978–0–06–228325–2.

B. Anita, 2023,

VAJZA N’KUTI (Tumblr), [online]

https:

PRIETO ROBERT, Daniel, 2023, Favourites Directory, (Notion), [online] https:

LABUSCHAGNE, Hanno, 2023.03.16, WhatsApp adds text detection feature for images, MYBROADBAND [online]

https:

COPELAND, Gemma, 2023,

Writing, GEMMA COPELAND [online] https:

CHERNISHEV, Innokenty,

Private Collection of Cigarette Packs, C-PACKS [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

APPLETON, Maggie, 2020,

A Brief History & Ethos of the Digital Garden, Maggie Appleton [online] https:

SCHRANZ, Christine (ed.), 2023. Commons in design. Amsterdam: Valiz. ISBN 978–94–93246–31–7. [online] https:

J. DEW, Christopher, 2015, PostCapitalism: Rise of the Collaborative Commons, MEDIUM, [online] https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

MERRIAM WEBSTER,

Arena definition, Merriam Webster Dictionary, 2023, [online] https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

ARE

How do you describe Are

ARE

About, Are

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

Are

How do you describe Are

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

REINFURT, David, 2023,

a-r-e-n-a, Are

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

PASHINE, Aaryan, 2023,

Arena API Playground, [online]

https:

BRÜNING, Joscha, UNTERLUGGAUER, Benjamin, 2022, Hyperchannel [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.29]

SEU, Mindi, BROSKOSKI, Charles, IJEOMA, Ekene, 2017,

print

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.29]

TINY FACTORIES, 2023,

Arena-2-slides, [online]

https:

ARE

How do you use Are

(Open Channel) [online] https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

HILT, Florian, 2023,

Moodboard, Are

https:

WARDLAW, Baker, 2023,

∆ bell hooks – Will to Change, Are

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

COPELAND, Gemma, 2023, Gemma Copeland [Online]

https:

PELZER, Jonas, 2023,

Collected, [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

ART FUNDAMENTS, 2023,

Art Fundaments, Are

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

ART FUNDAMENTS, 2023,

Art Fundaments, [online]

https:

BROSKOSKI, Charles, 2019. Creating the new social web,

The Conference [online]. Malmö, Sweden. 28 August 2019.

Retrieved from : https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25].

MAHLER-ANDERSEN, Frederik, 2023, Switzerland, Are

(open channel) [online] https:

RAO, Ventakesh, 2019,

The Extended Internet Universe, Ribbonfarm Studio [online]

https:

HYPHA COOP, 2021,

Digital Garden, [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

HAMON, Amaury, 2023,

Digital Gardeners, Are

(Open Channel), [online] https:

BENSON, Buster,

The Piles, Buster’s Notes, [online]

https:

CRITCHLOW, Tom,

Welcome to wikifolder, Tom Critchlow, [online] https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

BISCARDI, Christopher,

Digital Garden, All Chris’ Writing, [online] https:

VOLOBOEV, Nikita,

My Knowledge Wiki, Everything I Know, [online]

https:

BRANWEN, Gwern,

Gwern

https:

PARECKI, Aaron,

WEBMENTION [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

HAMON, Amaury, 2023,

CODE 101, [online]

https:

ZHAO, Jacky, 2023,

jzhao.xyz, [online]

https:

ZHAO, Jacky, 2023,

Quartz 4.0, Quartz, [online]

https:

consulted: 2023.11.25]

SCHWULST, Laurel, 2018,

My website is a shifting house next to a river of knowledge. What could yours be?, THE CREATIVE INDEPENDENT, [online]

https:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

R. CARPENTER, J., 2015,

A Handmade Web, LuckySoap, [online] http:

[consulted: 2023.11.25]

Thanks

For their contribution to

Gemma Copeland

Lucas Erin

Florian Hilt

Frederik Mahler-Andersen

Jonas Pelzer

Émilie Pillet

Daniel Robert Prieto

Aurélie Vial

Baker Wardlaw

For their advice and help to

Clément Lambelet

Julie Lang

Anthony Masure

Nicolas Nova

Daniel Sciboz

Tibor Udvari

Joël Vacheron

HEAD Media Design 23–24 Gang

Original Development & Design

This website exists thanks to the original work of Julien Bidoret who developped PageTypeToPrint, a paged

The timeline showcased in chapter 1 is based on Julie Blanc’s Original Timeline of technologies for publishing (1963–2018), many thanks to her for allowing the share and remix through open-source code.

Custom Development & Design

Translations

Proofreading

Fonts

SD-Walla, by Baptiste Lecanu (Spectrodrama).

OCR-X, by Eurostandard, Maxitype.

License

All text contents are licensed CC BY-NC-SA

Creative Commons: Attribution

All necessary efforts were taken to contact owners of the present images. If an error or omission happens, feel free

to write me an email.

LAWSON, Mark, Berners-Lee on the read/write web,

BBC News [online], 9 August 2005, http:/ [consulted: 16 October 2023] &/ news .bbc .co .uk /2 /hi /technology /4132752 .stm #8617;& #65038; STATCOUNTER GLOBALSTATS, Desktop vs Mobile vs Tablet Market Share Worldwide, Statcounter GlobalStats [online chart], September 2023, https:

/ / gs .statcounter .com /platform -market -share /desktop -mobile -tablet /worldwide

[consulted: 16 October 2023] ↩& #65038; LIALINA, Olia et al. (eds.), 2009. Digital Folklore: to computer users, with love and respect. Stuttgart: merz & solitude. Projektiv. ISBN 978–3–937982–25–0. [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ monoskop .org /images /9 /91 /Lialina _Olia _Espenschied _Dragan _eds _Digital _Folklore _2009 .pdf #8617;& #65038; ERTZSCHEID Olivier, 2013, Qu’est-ce que l’identité numérique? Enjeux, outils, méthodologies, Marseille, OpenEdition Press, series: « Encyclopédie numérique »,

69 p., ISBN 978–2–8218–1337–3. ↩& #65038; KRIM, Tariq, 2023, Slow Web [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.27] &/ www .slowweb .io /fr / #8617;& #65038; ODELL, Jenny, 2019. How to do nothing: resisting the attention economy. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

ISBN 978–1–61219–750–0. ↩& #65038; BROSKOSKI, Charles, 2019. Creating the new social web,

The Conference [online]. Malmö, Sweden. 28 August 2019. Retrieved from: https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25]. &/ videos .theconference .se /charles -broskoski -creating -the #8617;& #65038; LOVINK, Geert, 2021, Notes on the platform condition,

Making and Breaking. [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.23] &/ makingandbreaking .org /article /notes -on -the -platform -condition / #8617;& #65038; BEYENS, Ine et al., 2020. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent.

Scientific Reports. Vol. 10, no.1, p. 10763.

DOI 10.1038 . &/s41598–020–67727–7 #8617;& #65038; MERRIAM WEBSTER, Definition Garden, [online]

https:/ / www .merriam -webster .com /dictionary /garden

[consulted: 2023.11.27] ↩& #65038; R. CARPENTER, J., 2015, A Handmade Web, LuckySoap.

[online] http:/ / luckysoap .com /statements /handmadeweb .html

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; BERNSTEIN, Mark, 1998. Hypertext Gardens [online]

http:/ / www .eastgate .com /garden /Gardens .html

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; CAULFIELD, Mike, 2015, The Garden and the Stream, a Technopastoral, HapGood, [online] https:

/ / hapgood .us /2015 /10 /17 /the -garden -and -the -stream -a -technopastoral /

[consulted: 2023.11.27] ↩& #65038; NOVA, Nicolas, 2021. Enquête/Création en design. Genève: HEAD Publishing. Manifestes, 2. ISBN 978–2–940510–47–4. &

#8617;& #65038; HAMON, Amaury, 2023. TTTHESIS: TOOLS, Are

.na [online] https:/ / www .Are .na /amaury -hamon /ttthesis -tools

[consulted 2023.11.25]. ↩& #65038; LE GUIN, Ursula K., YI, Pul and HARAWAY, Donna, 2019.

The carrier bag theory of fiction. London: Ignota.

ISBN 978–1–9996759–9–8. ↩& #65038; SEU, Mindy, 2021. On Gathering. Shift Space [online].

No.1. https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ issue1 .shiftspace .pub /on -gathering -mindy -seu #8617;& #65038; HAMON, Amaury, Timeline of technologies and services for online creative research (1963–2023), [online]

https:/ / amauryhamon .github .io /Timeline -Web -Platforms /

[consulted: 2023.11.27] ↩& #65038; MERRIAM WEBSTER, Collection definition, Merriam Webster Dictionary, 2023, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .merriam -webster .com /dictionary /collection #8617;& #65038; OBRIST, Hans Ulrich, 2014. Ways of curating.

First American edition. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc.

ISBN 978–0–86547–819–0. ↩& #65038; CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, Mihaly, 2013. Creativity: the psychology of discovery and invention. First Harper Perennial modern classics edition. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics. ISBN 978–0–06–228325–2. &

#8617;& #65038; B. Anita, 2023, VAJZA N’KUTI (Tumblr), [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ inspirimgrafik .tumblr .com #8617;& #65038; PRIETO ROBERT, Daniel, 2023, Favourites Directory, Thisisgrey (Notion), [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ thisisgrey .notion .site /Favourites -directory -c10bf6c6701540c387ce1ebfb1135a4c #8617;& #65038; LABUSCHAGNE, Hanno, 2023.03.16, WhatsApp adds text detection feature for images, MYBROADBAND [online]

https:/ [accessed: 2023.11.25] &/ mybroadband .co .za /news /software /484119 -whatsapp -adds -text -detection -feature -for -images .html #8617;& #65038; COPELAND, Gemma, 2023, Writing, GEMMA COPELAND [online] https:

/ [accessed: 2023.11.25] &/ gemmacope .land /writing / #8617;& #65038; CHERNISHEV, Innokenty, Private Collection of Cigarette Packs, C-PACKS [online] https:

/ / www .c -packs .com /

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; APPLETON, Maggie, 2020, A Brief History & Ethos of the Digital Garden, Maggie Appleton [online]

https:/ / maggieappleton .com /garden -history

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; SCHRANZ, Christine (ed.), 2023. Commons in design. Amsterdam: Valiz. ISBN 978–94–93246–31–7. [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ valiz .nl /images /Commons -in -Design .pdf #8617;& #65038; J. DEW, Christopher, 2015, PostCapitalism: Rise of the Collaborative Commons, MEDIUM, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ medium .com /basic -income /post -capitalism -rise -of -the -collaborative -commons -62b0160a7048 #8617;& #65038; MERRIAM WEBSTER, Arena definition, Merriam Webster Dictionary, 2023, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .merriam -webster .com /dictionary /arena #8617;& #65038; ARE

.NA TEAM, How do you describe Are.na at a party?

Are.na (Open Channel) 2021, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /block /14492467 #8617;& #65038; ARE

.NA , About, Are.na [online] https:/ / www .Are .na /about

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; Ibid. &

#8617;& #65038; Are

.na TEAM, How do you describe Are.na at a party? Are.na (Open Channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /Are .na -team /how -do -you -describe -Are .na -at -a -party #8617;& #65038; REINFURT, David, 2023, a-r-e-n-a, Are

.na (Open Channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /david -reinfurt /a -r -e -n -a #8617;& #65038; PASHINE, Aaryan, 2023, Arena API Playground, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.29] &/ playground .a -p .space / #8617;& #65038; BRÜNING, Joscha, UNTERLUGGAUER, Benjamin, 2022, Hyperchannel [online] https:

/ / hyperchannel .net /

[consulted: 2023.11.29] ↩& #65038; SEU, Mindi, BROSKOSKI, Charles, IJEOMA, Ekene, 2017,

print.are [online] https:.na / / print .Are .na /

[consulted: 2023.11.29] ↩& #65038; TINY FACTORIES, 2023, Arena-2-slides, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.29] &/ arena2slides .herokuapp .com / #8617;& #65038; ARE

.NA COMMONS, 2023, How do you use Are.na ?, Are.na

(Open Channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /Are .na -commons /how -do -you -use -Are .na #8617;& #65038; HILT, Florian, 2023, Moodboard, Are

.na (Public Channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /florian -hilt /moodboard -57offqyw3oi #8617;& #65038; WARDLAW, Baker, 2023, ∆ bell hooks – Will to Change, Are

.na (Public Channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /b -wardlaw /bell -hooks -will -to -change #8617;& #65038; COPELAND, Gemma, 2023, Gemma Copeland [Online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ gemmacope .land / #8617;& #65038; PELZER, Jonas, 2023, Collected, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ collected .li / #8617;& #65038; ART FUNDAMENTS, 2023, Art Fundaments, Are

.na (Group), [online] https:/ / www .Are .na /art -fundaments /

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; ART FUNDAMENTS, 2023, Art Fundaments, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ artfundaments .ch / #8617;& #65038; BROSKOSKI, Charles, 2019. Creating the new social web,

The Conference [online]. Malmö, Sweden. 28 August 2019. Retrieved from : https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25]. &/ videos .theconference .se /charles -broskoski -creating -the #8617;& #65038; MAHLER-ANDERSEN, Frederik, 2023, Switzerland, Are

.na

(open channel) [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /frederik -mahler -andersen /switzerland -gfjaruqpf40 #8617;& #65038; RAO, Ventakesh, 2019, The Extended Internet Universe, Ribbonfarm Studio [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ studio .ribbonfarm .com /p /the -extended -internet -universe #8617;& #65038; HAMON, Amaury, 2023, Digital Gardeners, Are

.na

(Open Channel), [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .Are .na /amaury -hamon /digital -gardeners #8617;& #65038; HYPHA Coop, 2021, Digital Garden, [online]

https:/ / digitalgarden .hypha .coop /protocol

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; BENSON, Buster, The Piles, Buster’s Notes, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ busterbenson .com /piles #8617;& #65038; CRITCHLOW, Tom, Welcome to wikifolder, Tom Critchlow, [online] https:

/ / tomcritchlow .com /wiki /

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; BISCARDI, Christopher, Digital Garden, All Chris’ Writing, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ www .christopherbiscardi .com /garden #8617;& #65038; VOLOBOEV, Nikita, My Knowledge Wiki, Everything I Know, [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ wiki .nikiv .dev / #8617;& #65038; BRANWEN, Gwern, Gwern

.net , [online] https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ gwern .net / #8617;& #65038; PARECKI, Aaron, WEBMENTION [online] https:

/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ webmention .io / #8617;& #65038; HAMON, Amaury, 2023, CODE 101, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ teaching .amauryhamon .com / #8617;& #65038; ZHAO, Jacky, 2023, jzhao.xyz, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.27] &/ quartz .jzhao .xyz / #8617;& #65038; ZHAO, Jacky, 2023, Quartz 4.0, Quartz, [online]

https:/ [consulted: 2023.11.25] &/ jzhao .xyz / #8617;& #65038; SCHWULST, Laurel, 2018, My website is a shifting house next to a river of knowledge. What could yours be?, THE CREATIVE INDEPENDENT, [online] https:

/ / thecreativeindependent .com /essays /laurel -schwulst -my -website -is -a -shifting -house -next -to -a -river -of -knowledge -what -could -yours -be /

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038; R. CARPENTER, J., 2015, A Handmade Web, LuckySoap,

[online] http:/ / luckysoap .com /statements /handmadeweb .html

[consulted: 2023.11.25] ↩& #65038;